Old Longtang Rowhouses front a landscape of new skyscrapers on Maoming North Road

Yesterday I brought two groups of NYU students out on separate field trips which converged at the famous Old Jianjiang Hotel. This hotel is famous for hosting high level parties and delegations of officials from China and abroad. Mao used to stay there during his visits to Shanghai. It is also the place where Nixon and Kissinger and their team met with Zhou Enlai and other top officials to sign the Shanghai Communique. The hotel is located on Maoming South Road. A few blocks north of the hotel is a historic house and museum dedicated to the memory of Chairman Mao.

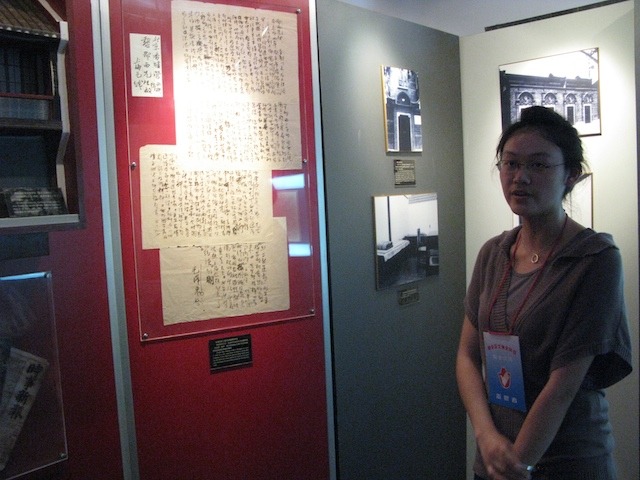

I met my first group of students from my Modern Chinese History course at the Mao House, where the young revolutionary lived with his first wife Yang Kaihui and their sons Anying and Anqing in 1924.

The house has been restored of course, and is run as a museum dedicated to the life and career of Mao. The entrance is fairly low-key and one can pass by easily without knowing that this site exists. I did so for years before I finally ventured through the main entrance gate. I discovered the Mao House last year and decided to incorporate it into my class field trips.

Entering the house, one can see the living room, bedroom and kitchen where Mao and his family resided for six months. Life-size wax figures of Mao and his wife and children may be seen in the bedroom. The kitchen contains the rudimentary stove and other implements common to that era.

Heading upstairs, accompanied by two young female guides who worked there once per week (they were college students), we toured the museum. There are several original documents penned by Mao himself, including some meeting notes and a letter to his teacher in Beijing.

The first room traces Mao's development as a young revolutionary and his involvement in the early years of the CCP and their four-year alliance with the KMT from 1923-1927. The second room examines Mao's revolutionary career in Yan'an and post-1949 when he became the nation's Helmsman. A set of portraits of Mao over those decades hangs over a dual image on the main wall connecting the rooms.

The image comes together from two angles, one showing a desolate snowy landscape symbolizing China prior to 1949, and another showing a burning sun rising amidst a panoply of red leaves, signifying the post-1949 era.

While there is little mention of the Great Leap Forward or Cultural Revolution, there are many signs and clues of these two eras. There are several photos of Mao inspecting Shanghai's modern industries, including a machine factory and a steel mill in 1957, signifying the aspiration of Mao to rapidly modernize the country while maintaining an independence from the Western world--an aspiration that would lead to some disastrous consequences in the years 1958-61, the era of the Great Leap Forward. While the Cultural Revolution is not mentioned per se, there is a letter on the wall from the Chairman to one of his old friends from Hunan, a professor in Shanghai.

One of the guides told us that the professor's home was ransacked by zealous Red Guards in the early years of the GPCR (1966-1968), but when they found this letter showing his relationship to their Great Hero, they stopped harassing him. The final room of the hall is dedicated to the memory of Mao's son Anying, who was killed in North Korea during the Korean War (1950-1953) and whose body still lies there. A pair of sculpted bronze hands holds up a small mound of North Korean soil in homage to the martyrdom of Mao's son during that horrible war.

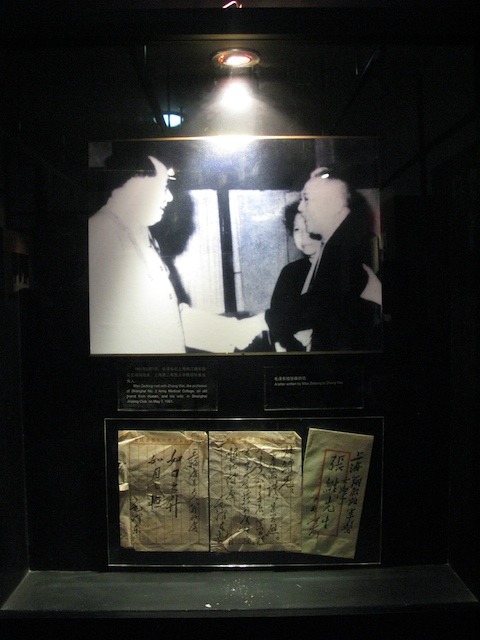

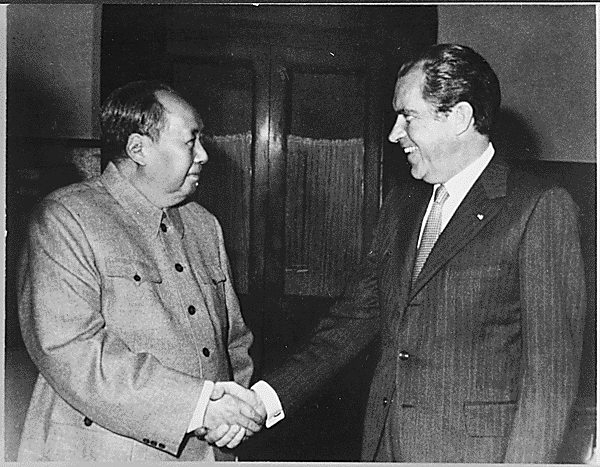

The Korean War was the nadir of Sino-American relations which had quickly deteriorated in 1949 when America chose to support the renegade government of Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan. The thaw began when Nixon staged an unprecedented visit to the PRC, where he met with Mao in February 1972. The handshake between America's notorious anti-Communist president and one of the great icons of global communism was indeed a historic event of magnificent proportions.

Making our way down Maoming Road to the Old Jinjiang Hotel, after a brief rest stop at the Citizen Cafe on Jinxian Road. As it turns out, most of my students hadn't had lunch so this was a very good decision.

A Time Magazine photo of Nixon's historic visit. While he didn't bother to learn Mandarin, Nixon brushed up for the visit with many lessons in the art of eating with kuaizi (chopsticks).

After our lunch break, we visited the Great Hall, built in 1959 and rebuilt in 1998, where Nixon and Zhou had met in 1972 to draft the Shanghai Communique.

We went inside the hall and gathered briefly in the banquet hall, where a wedding banquet was in preparation. It was there at this consecrated spot that Nixon had raised a drunken toast to a new era of Sino-American relations that would lead to the China that we live in today.

I brought a copy of the Shanghai Communique and asked the students to read it out loud, each one taking a paragraph. We then discussed how both sides navigated the key issue of Taiwan's status, agreeing to differ while also forging a new basis for normalization of relations.

Seven years later, under President Carter and Chairman Deng Xiaoping's watch, relations were indeed normalized and embassies once more activated. Regardless of this important episode in modern world history, which has recently been written up in a wonderful book called Nixon and Mao (I picked up a copy at the Beijing Bookworm and lent it to a student last week in my Mao course), the Jinjiang Hotel is well worth a visit.

The grounds are exquisite and the hotel originally built in the 1930s is stately and grand. On the second floor of the main lobby is a wonderful cafe with a skylight giving you a view of the hotel rising up into the air. After my first group of students departed at four pm, I met a couple of friends there on a business matter. A Chinese pianist played some familiar if cliche tunes while we talked business.

Then around 5:30 my second group of students showed up. Out of the six students in my Mao seminar, only three showed up--the two Chinese women in my class were both working and the other was ill. So it was a boys night out. I brought them over to the Great Hall, where the wedding party was now beginning to show up. We poked our heads into the banquet hall briefly but did not want to disturb the party. When I asked him if this was indeed where Nixon and Zhou held court over the Communique, a guard at the door confirmed this, then he led us to an adjacent room where a small model of the original building from 1959 stands in a glass case.

So it isn't exactly where they met, but close enough. The plan was for us to hold some sort of memorialization of the event, but I hadn't really thought through carefully enough how that could be done, and the wedding banquet completely derailed those plans in any case. So we moved on to Plan B, which was to head up the road to a nearby Hunan restaurant called Di Shui Dong. What better place to commemorate the Mao Years than with a tasty meal from Mao's home province.

The Chairman would certainly have approved of this executive decision, and he might have even enjoyed the Belgian ale that this fine establishment offers to its customers.