Greg Girard is a professional photographer who has made Shanghai his home for the past nine years. I first met Greg in 1999. In 2000, Greg and I were both photographing the city in flux, documenting the rapid changes as the old city built during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was being bulldozed to make way for the new city of the 21st century.

I have great respect for commercial photographers who engage in long-term personal projects documenting historical and social processes of global significance. In this respect, Greg’s work ranks up there with that of Sebastiao Salgado in terms of its overall concept of a world in flux, even if it is far more focused on one city and less people-oriented than Salgado’s brilliant work. Inspired partly by Salgado, my own project began and ended in 2000, resulting in a few thousand black and white images, focusing mainly on people and places in Shanghai caught up in the whirlwind of change at the dawn of the twenty-first century. (I have yet to publish or show these images in public--they are still undeveloped for the most part)

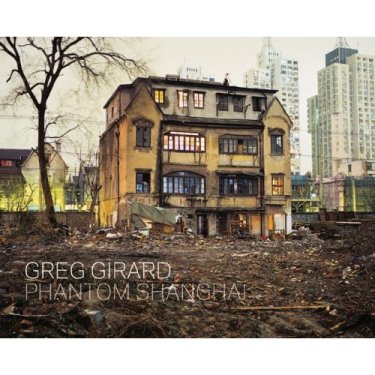

Greg started in black and white but moved to color and continued to document the transformation of the built environment over the next six years using medium format cameras and a tripod. The result is a stunning collection of 130 color photographs published in the book Phantom Shanghai (Magenta Foundation, 2007). Not only are these photos astonishing in terms of their technicality, but they also reflect a unique eye for detail and an intimate knowledge of the urban fabric of Shanghai’s exterior and interior worlds. The traveling exhibition of enlarged photos associated with Greg’s project is a magnificent display of the technical accomplishments and compositional brilliance of Greg’s work. Viewing these photos firsthand, one feels that one could reach in and touch the objects and walk through the scenes of a city that is rapidly vanishing and being replaced by another city. Thus there is a ghostlike feeling to these images. There is also a feeling of ineffable sadness as one confronts the stark passage of time—a deep sense of loss accompanied by an excitement and anxiety about what the future holds for this city and country.

Last month I wrote to Greg and asked him a series of questions about this photo project. Here are his answers.

AF: Your book _Phantom Shanghai_ is an amazing juxtaposition of old and new in a city that has undergone rapid transformation since the 1990s. As you've mentioned in another interview, this is a well-trodden subject. How do your images differ from other photographic portrayals of the city in flux?

GG: Perhaps by starting from the point of view that it’s a historical accident that as much of the early 20th century city was preserved as long as it was. Much of Shanghai was preserved by neglect after 1949, when urban development for profit came to a halt following Mao’s victory. There was a kind of centrally-planned stasis -at least in urban development terms- for more than four decades. Equally, Shanghai’s sudden growth in the 1990s was also a centrally-planned directive, when Deng Xiaoping dictated that city should “catch up” (with southern cities like Shenzhen). And so I saw this time that we were living through as a kind of phenomenon where both Shanghais were in evidence: the neglected early 20th century city (and its rubble) literally illuminated by flood-lit towers of the new city going up all over the place.

The other thing I wanted to show was what it was like to live in these houses and apartments originally built for single families but later (after 1949 and during the Cultural Revolution) subdivided to accommodate many more people than originally intended.

From the outside many of these places can look quite grand, in a faded sort of way, but on the inside the conditions can be quite dire. A general lack of upkeep over the decades has given them a patina comprised of layers of peeling paint, dust and cooking grease. So, I wanted to show the insides of these places and what was a very normal way to live for a couple generations of Shanghainese: the shared kitchens and bathrooms, the relative lack of privacy, the sense of lived-in-ness.

AF: What can you tell us about the technical process of capturing these photos, especially the night photos, which are stunningly clear and colorful despite the low lighting conditions?

GG: The photographs were taken on medium format (120) daylight transparency film. Because the film is balanced for daylight it registers artificial light somewhat unnaturally, hence the colour shifts, which occur when photographing at dusk or at night when the lighting sources are entirely artificial. I used a tripod most of the time as the exposures are quite long: from one second to five or ten minutes.

AF: What camera or cameras did you use to capture these images? How did you plan out a photo session?

GG: I mostly used a Mamiya 7 rangefinder, which is light but not very well suited to anything “architectural” because the viewfinder gives only a rough approximation of what the camera lens will register. I also used a Fuji 6x8 camera, which is much larger and heavier.

Some of the locations were planned and arranged in advance, others I came across as I wandered around.

I asked friends to introduce me to their friends and relatives living in older buildings, and so I had a lot of help in that regard; other times I would see some place that looked interesting and my assistant and I would get talking to someone and ask them to let us have a look inside. It was quite hit and miss. But people were mostly friendly even if they wouldn’t agree to let me photograph inside. Hostility was rare though there are always a few nasty ones.

AF: One of your photos is of mailboxes in and old apartment building. When I saw that photo, my immediate reaction was: this is a photographer who really understands Shanghai. A lot of photographers, even great ones like Sebastiao Salgado, have come to the city and shot photos that end up looking like glorified tourist shots, even if they are technically or compositionally brilliant. Yet your photos go much deeper into the physical realities of the city. What can you tell us about the process by which this book evolved? How long did you work on collecting these photos? How did you choose the

ones that made it into the book? Did you have help in doing so?

GG: I started the project in 2000 in black and white and then after a year I felt that was a mistake and switched to colour. So the photographs were taken between 2001 and 2006. In 2005 I had a solo show in Canada (at Monte Clark Gallery in Toronto) and that’s where my publisher MaryAnn Camilleri first saw the work and invited me to do a book. Around mid 2006 I presented my own edit of around 600 photographs (out of thousands) to MaryAnn and the book designer Gilbert Li, and from there we worked it down to the 130 that are in the book. The final edit was a collaborative effort; and the sequencing, which I am very pleased with, is mostly the work of Gilbert Li.

AF: Some people might critique your book for not having images of people. There are a few in there, such as the barbershop photo, but mostly these are images of places, buildings, and objects, not people. Why didn't you choose to work more with people for this book?

GG: If you look at a photograph of a room, for example, with a person in that room, I think you tend to notice the person more than the room. I wanted to photograph the Shanghai that isn’t going to survive the vision the place has for itself. And I felt that trying to photograph the evidence of the hard flow of time through the city could best be done by paying attention to that evidence. I’m not really sure how much you can tell about a person in a photograph anyway. And so, if there were more people in the book, then it would have been a book about the kind of haircuts and clothes people had in Shanghai from 2001 to 2006, and that might be an interesting book but it wasn’t the book I wanted to do.

AF: How have Shanghainese people reacted to your book and your traveling exhibition of enlarged photos? How has the reaction been in Beijing, where the exhibition was held at 798 last month? Do you see a difference in the reactions of Chinese in Shanghai and elsewhere? Do they "get" your photos?

GG: Most Shanghainese I’ve spoken to have said that this is the Shanghai they grew up in. They understand the pictures to be a kind of tribute to the city as much as they are a partial and subjective record. Once in a while though I hear people say I’m making Shanghai look bad. There is still some defensiveness from some people about a foreigner taking pictures of anything that’s less than flattering. It used to be worse though. When I first began the project there used to be obstreperous Neighborhood Committee ladies guarding the entrances to lanes and alleys. Maybe they’re still there but with so many foreigners wandering around the city these days they’re used to it and don’t bother me anymore.

AF: Final question: Who is the intended audience for your book?

GG: I wanted to make pictures about the Shanghai that I knew and was interested in, and that I wasn’t seeing in any of the many books about the city. Most of them had an overtly nostalgic point of view, which was exactly what I didn’t want in my pictures. That’s why I’m so thrilled William Gibson agreed to write the foreword. I knew that someone like him, coming at it from the completely opposite direction, even without ever having visited, would understand the strange rare intensity of this very specific time and place.

I realized that there would be a resident audience for any book that came out of the pictures, but I wasn’t thinking really about any specific audience. I mean that if the pictures were interesting enough I hoped they would be interesting to anyone, whether they knew Shanghai well or not at all. Of course I’m extremely pleased when I hear someone who knows the city well tell me that the pictures really match the Shanghai they live in. That’s what I tried to do for myself.

Here is more info on Greg Girard, taken from his own website:

http://www.greggirard.com/home.htm

Greg Girard, based in Shanghai, is a Canadian photographer recording the changes taking place in China and across Asia for leading editorial and corporate clients.

Between 1987 and 1997 he established himself as a photographer based in Hong Kong, represented by Contact Press Images (NY), from where he photographed on assignment across Asia. In 1993 he published the book "City of Darkness", a document of the final years of the Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong, in collaboration with Ian Lambot. In 2002 he launched the picture agency documentCHINA, in collaboration with Fritz Hoffmann, an online archive specializing in contemporary photography from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Editorial Clients: _Time, Newsweek, Fortune, Businessweek, Forbes, Elle, Figaro, Paris Match, Stern, Der Spiegel, NY Times Magazine, and other magazines and newspapers worldwide.

Corporate Clients:_Ove Arup, Foster and Partners, K Plus K Architects HK, Thames Water, Solectron, United Airlines, Warner Lambert

Books:_"City of Darkness; Life in Kowloon Walled City"; Watermark Publications

Exhibitions:_Kwangju Biennale; Kwangju, South Korea, 1997_Cities on the Move; Hayward Gallery, London, 1999_Cities of the 21st Century; Bauhaus, Dessau, Germany, 2000_Cities on the Move; Kiasma, Helsinki, 2001_Kowloon Walled City, with Ian Lambot; Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture Gallery, New York, 2003_"Hong Kong-Shanghai"; Parallel Worlds, Lille, European Cultural Capital 2004.