Every year’s end, I post an annual review of books I read over the past year that made a deep impression on me. Last year (2020) was a reading bonanza for me, but that was a special year, a year of removing oneself nearly completely from social engagements outside of one’s immediate family—at least for the six months when we were sheltering in Mass. Reading took over as a mainstay of my pandemic days. That and long nature walks in nearby forests and wildlife preservation areas.

This year (2021) was different. Back in China, it was back to business for the most part, and back to heavy socializing, especially in Shanghai. In addition to a full teaching load, I spent most of the past year in the editing room working on my doc film on Shanghai’s jazz history. And there was the usual assortment of articles to write and books and articles to review, students to advise, recommendations to write, etc. etc. Even so, I did manage to squeeze in some pleasure reading here and there, mainly in the odd hours of the evening. Here are the highlights of my reading year.

The two novels I read this year that took the greatest effort and reaped the greatest rewards were both family sagas. Many decades ago, while a student in Taipei Taiwan, I had read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s famous novel One Hundred Years of Solitude about a family located in the fictitious town of Macondo deep in the heart of South America. I had some dim memories of the characters and the story, but now I felt it was high time for a reread, and honestly upon opening the book for a second time it felt like I had never read it before. Did my memory play tricks with me? I did recall the ascension of Remedios the Beauty, but little else in this fantabulous story. In any case, it was quite an experience to re-immerse oneself in the rich and surreal world of the Buendia family in the town of Macondo and their loves, losses, trials and tribulations across a century of time. The repetitions of character, the buildup of family history, the dark secrets and revelations, the tragic flaws, the grand landscape of history, and above all, the lush descriptions of their house and home and its slow but inevitable decay over time make this book a remarkable and singular reading experience. There’s something deeply philosophical about this novel and its treatment of time, character, nation, and family, which is perhaps why I reminisced about it now and then over the years and why it drew me back in for another read.

The second family saga I tackled was the wartime novel The Makioka Sisters (known in Japanese as細雪, Sasameyuki, "light snow") by Junichiro Tanizaki 谷崎潤一郎. The story takes place around the beginning of World War II, focusing on a rather traditional Japanese family composed of four sisters, who live in both Osaka and Tokyo. I am a huge fan of Tanizaki and I have read many of his other works, including Naomi (the story of a femme-fatale café waitress in 1920s Tokyo), and Some Prefer Nettles (蓼喰う虫, Tade ku mushi) and this book has been sitting on my shelf for decades, waiting for me to get around to it. Upon opening it, one is immediately pulled into the social world of this semi-affluent yet declining Japanese family and their dramas, which center around the family’s desire to marry off the two younger sisters. The main character of the novel appears to be the second sister Sachiko, who tries to hold the family together while dealing with the inability of the quiet and delicate third sister Yukiko, now aging past 30 (an unmarriagable age even today in Japanese and most Asian societies) to find a marriage partner, despite numerous attempts at miai (marriage proposal meetings) with various eligible bachelors. Meanwhile, fourth sister Taeko proves to be the most troublesome one of all. She represents the freer spirit of the younger generation, and her complicated relations with various men in her life threatens to cast a pall upon the family’s honorable name. Eldest sister Tsuruko observes these shenanigans from a distance from the “main home” in Tokyo, occasionally intervening or at least offering her advice on matters. Though more compressed than the century-long saga of One Hundred Years of Solitude, we similarly follow a family through various crises, including the mounting war abroad, which is having a greater impact on the domestic Japanese economy. And we see them struggle through various acts of nature including—one of the best scenes in the novel—a torrential flood that nearly sweeps away one of the family members. As well as a keen observer of the landscape and the environment, Tanizaki has an amazing ability to capture the interior lives and thoughts of these women as they bravely face these dangers, challenges, and crises. At the same time, the novel is a primer in the nuances of Osaka and Tokyo language, customs, and culture, particularly the customs surrounding marriage proposals. For Japanophiles, this is an absolute must-read.

Speaking of Japanophilia, I also reread two novelettes by another of my favorite Japanese authors, Nagai Kafu 永井荷風: “During the Rains” and “Flowers in the Shade.” I first discovered his story “During the Rains” nearly 20 years ago, while researching materials for my course on nightlife, which covers Tokyo as well as Shanghai, New York, and Paris. Like Tanizaki’s Naomi, this story also focuses on a young Japanese café waitress or jokyu 女给named Kimi, who works in a café in Ginza, Tokyo’s most modern district in the 1920s. The story occurs not long after the famous earthquake of 1923, and the entire city is in process of rebuilding. Café culture is blossoming, and it is a shallow ruse for a kind of soft sex industry that Japan became quite famous for over the next century, and which indeed has its deep roots in the courtesan quarters and geisha cultures exemplified by the Yoshiwara in old Edo (the city that became Tokyo). The story follows her relations with her male customers, including one who secretly seeks “revenge” for her lascivious lifestyle (even though that is part and parcel of her career as a café waitress) by publishing intimate details about her in the local press. This reminds me of the so-called “mosquito journals” of Shanghai at the time which published articles about the lives and loves of courtesans and later dance hostesses. In fact, the café waitress resembles the dance hostess or wunu 舞女of Shanghai (and of Japan) in many ways. “Flowers in the Shade” follows the story of a man and his wife, who basically engages in prostitution to support the family. Kafu’s work and his eye for details can be compared with that of Mu Shiying, the novelist whose stories of 1930s Shanghai we translated for the book Mu Shiying: China’s Lost Modernist. Translating those stories was quite a task, and the same must have been true for Kafu’s works which describe in fascinating detail the local spaces and places of 1920s Tokyo. Lane Dunlop’s translation is remarkable. This is another book well worth adding to one’s personal library.

This past summer, I embarked on a month-long journey deep into the interior of China. For pleasure reading on my journey, I chose to read Jack Kerouac’s classic book The Dharma Bums. This autobiographical account of a wandering vagabond beat poet in 1950s America begins with a journey by rail along the California coastline. It ends with a two-month stint atop an isolated mountain peak in Washington State. In between we encounter a wild cast of characters, most notably the poet Japhy Ryder, who is based on the real poet Gary Snyder. The book is a poetic masterpiece and a gem of modern fiction. Couldn’t be a better reading companion as I headed into the vast deserts of western China and then on to the Tibetan highlands where we climbed mountains and toured monasteries with a group of hardy adventurers.

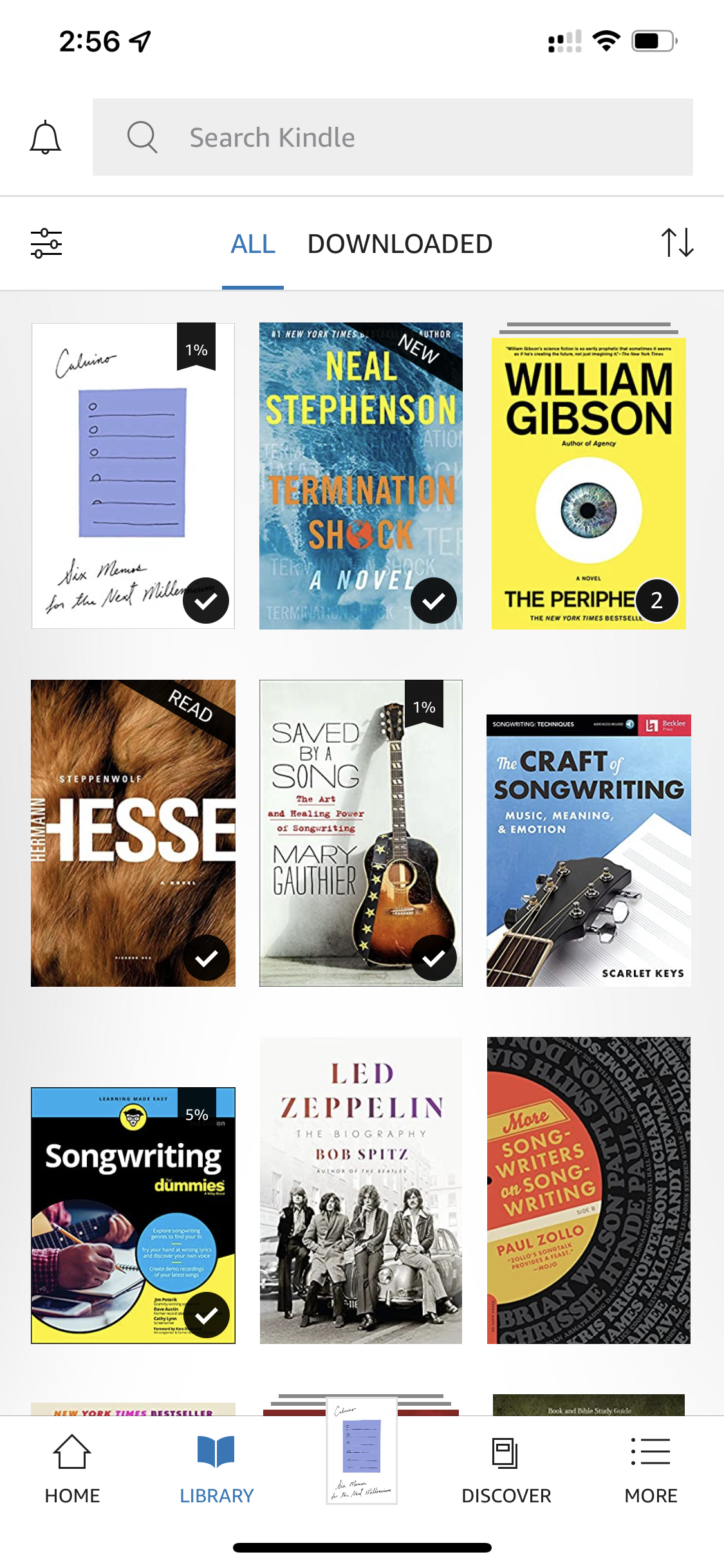

After that I decided to revisit another old classic in my personal collection: Six Memos for the Next Millennium by Italo Calvino. I’ve been a fan of Calvino’s work since my college days, and this book is an encapsulation of his wisdom on the art of storytelling with examples drawn from centuries of literature. I remember finding it quite charming in college and decided it was worth reinvestigating. Sure enough, these lectures, originally delivered as a series of speeches at Harvard (or planned for that purpose) marked his final words of wisdom before his passage from the realm of the living. For any writer or artist, the book offers plenty of practical advice on the art of storytelling and how to frame and shape compelling stories. The six chapters are “Lightness,” “Quickness,” “Exactitude,” “Visibility,” “Multiplicity,” and “Consistency.” Perhaps this ought to be a rubric for those of us who teach creative writing (or songwriting in my case).

Another good read this year was the cyber-punk novelist William Gibson’s novel The Peripheral. I’ve been a fan of Gibson since the 1990s when he came out with the brilliant and prescient novel Neuromancer. The Peripheral tells the story of a brave young woman and her older brother, an ex-military badass dude, who live somewhere rural in southern USA in the near future, and are caught up with people from far-future London in a murder-mystery drama that leads to increasingly violent entanglements with super-connected, well-financed, and teched-out agents. In between these two epochs lurks the specter of a major disaster, some sort of ecological global crisis (sound familiar? This is the world we are lurching into now). The two worlds are connected by some inexplicable technology, which enables people to communicate back and forth through time and even interact in real time through bodies known as “peripherals,” which are autonomous robots in various states of technological development. Since people from the far future are influencing the past when they interact with it, this in turn creates “stubs,” which are alternate future trajectories. As usual with Gibson’s work, the plot isn’t as important as his rich descriptions of the technologies, people, mindscapes, and landscapes that he imagines in these worlds. Next on my list is the sequel to this novel, Agency.

Speaking of alternate mindscapes, earlier in the year I greatly enjoyed reading Michael Pollan’s book How to Change Your Mind, a non-fiction book about the history of psychedelics and the quest to use these drugs for medicinal and healing purposes. Pollan makes a very convincing argument for the positive use of psychedelic agents to help people treat a wide range of mental conditions such as anxiety, depression, and even facing one’s own impending death as in the case of terminal cancer patients. I was “turned on” to this book (a la Timothy Leary, who is featured in the story) by a podcast of the author’s interview with Terry Gross on “Fresh Air” (my favorite podcast of all time). One of the best features of the book is that Pollan doesn’t shy away from describing vividly his own experiences with psychedelic drugs, which was part of his research strategy for the book, and in my opinion, a totally necessary part.

This book is a good companion to T. C. Boyle’s novel, Outside Looking In, about the infamous Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary and his social experiments with LSD, psylocibin and other drugs. Boyle’s latest novel is told from the vantage point of a young man who joins Leary’s team of experimentalists, only to find himself caught up in a dizzying world of psychedelic overload, compounded by the sexual excesses of the late 1960s. The novel ends in the rural New York mansion in which Leary and his acolytes holed themselves up after being expelled from Harvard for their shenanigans. (I read this book last year during the early lockdown period the pandemic, but it somehow didn’t make my 2020 list of good reads, even though it was a good read indeed).

The title of Outside Looking In is an homage to the British rock band The Moody Blues (one of my favorite bands from the psychedelic era of the 1960s--I became familiar with this band because we had several of their records when I was growing up, thanks to my cool step-dad.) It is from their song about Timothy Leary: “Timothy Leary’s dead. Nononono he’s outside looking in.” Another band from that era is Steppenwolf, which takes its name from a famous novel by Herman Hesse, published in the 1920s. As a huge fan of Hesse’s work, I’d read Steppenwolf many times before. But now that I am the same age as the central character, Harry Haller, it was time to give it another read. The novel focuses on the male protagonist and his process of “enlightenment” so to speak. When the story he begins, he appears as a lost soul, a loner who loves to lose himself in books and wine. He rents a room in a townhouse, an attic room where he can indulge himself in drinking and reading from his prodigious personal library. (I can see myself in this character for sure.) Over time, he meets some interesting characters in the town where he has settled for the time being. One of them is a young woman named Hermine, who reminds him of a childhood friend named Herman. She eventually leads him on an unforgettable journey into a quasi-magical netherworld populated by party animals, musicians, and other people of the demimonde. Again, I sympathize with the character’s journey, an Orpheus-like descent into a mystical underworld of creativity and excess. Which is also a good description of the 1960s, the age (at the very end at least) in which I was born.

Those who have taken this dark and perilous road deep into the underworld and back to the surface return with knowledge and with sad tales to tell us. I will leave the reader of this blog with one final entry for my best reads of the year. Recently I was notified that a “mini-course” I proposed about songwriting has been approved by the Powers That Be. In March, I will be leading an intensive four-day course for our DKU students interested in learning about the art of songwriting. This is not a subject that I am well-versed in and my own attempts at songwriting over the years have been sporadic at best, so I will be going on this journey of exploration with them. In order to prepare for the course, I have been reading some books and articles on songwriting. The one that really stands out thus far is an autobiographical account by singer-songwriter Mary Gauthier, Saved by a Song. Not only does she offer hard-earned advice on how to craft and write a song, but she uses her songs as vehicles to tell stories about her own life and to share the painful process of self-enlightenment with others—and vice versa of course. Her songs reflect a life that was tragic from the outset, having been abandoned by her birth mother and adopted by a difficult set of parents to say the least. After a youth marked by various acts of defiance and delinquency, and after conquering her addictions to drugs and alcohol, and later to sexual partnerships that go nowhere, she goes on to confront some of her darkest demons stemming from her unfortunate childhood. Meanwhile, she learns how songwriting can be a mode of healing, atonement, and celebration of life’s challenges. I learned a great deal about songwriting from this book, and how behind every song there is a deeper one waiting to be revealed--if we only listen more closely to the songs of the demons and angels that are deep inside our souls. Or something to that effect.

That’s enough for now. So long, and happy readin’ folks!