Last night, publisher Graham Earnshaw and I had the pleasure to launch the republished memoir of 1920s Shanghai jazz musician, Whitey Smith. Whitey’s book I Didn’t Make a Million, first published in Manila in 1956, was just republished in its original form by Earnshaw Books. In the latest edition, I provide a brief introduction to the man and his times. During my talk, I played two songs recorded by Whitey Smith’s orchestra in 1928 that probably haven’t been heard in Shanghai since the 1930s.

Frank Tsai, organizer of the Hopkins China Forum talks, co-organized this event along with the Royal Asiatic Society. It was held at the Wooden Box. Here’s the announcement: At Hopkins China Forum, we next host Andrew Field of Duke Kunshan Unversity and Graham Earnshaw, publisher of Earnshaw Books, on Whitey Smith in Shanghai's Jazz Age: The Man Who Taught China to Dance. Andrew Field is a world expert on Shanghai's jazz age, and author of Shanghai Nightscapes and Shanghai's Dancing World. This talk will discuss this era and one of its seminal musicians, whose story has just been republished by Earnshaw Books. Thursday, May 18th, 7:00pm at Wooden Box. Please RSVP by reply. This talk is co-sponsored by the Royal Asiatic Society.

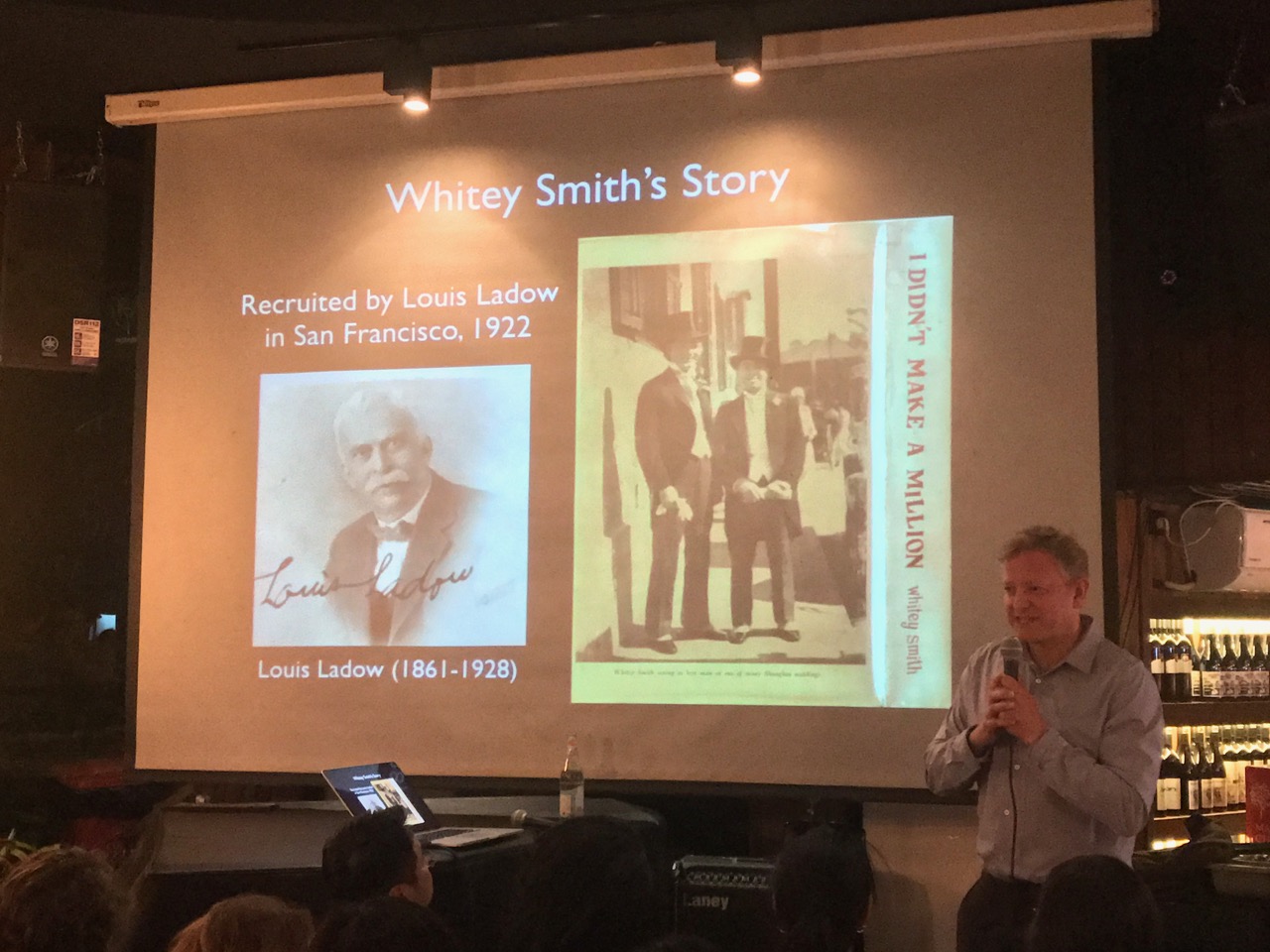

The event was well attended, with many familiar faces in the audience. I gave a short presentation on the story of Whitey Smith, starting with his arrival in Shanghai in 1922 on the behest of fellow American Louis Ladow, who was opening a new club, the Carlton Cafe, and wanted to ‘import’ an American jazz band to play there. As Whitey recounts in his memoir:

IN the year 1922 I knew just as much about China as China knew about me. I had been down in Los Angeles for a year playing the Coconut Grove in the Ambassador Hotel. I was back in San Francisco with Max Bradfield at Tait's, on O'Farrell Street, across from the Orpheum Theater. Upstairs was Fanchon and Marco's place called the Little Club. I got a job playing there when I wasn't working for Max, and this meant I had to move my drums twice a day. Rube Wolf was in charge at the Little Club. He was a brother of Fanchon and Marco, also a trumpet player and comedian.

The two jobs were a lot of fun but neither one was a sure thing because of prohibition. There were always rumors that the place would be transformed into a coffee shop and restaurant with no room for bottles under the table, so when I got up each morning I was always wondering whether I would have one job, two jobs or no job at all at the end of the day.

For several nights in a row I had noticed a steady newcomer among our clientele. He was six feet tall weighing around 220 pounds, handsome you could say, with silver-gray hair and a heavy military mustache. He didn't do much but sit at a table by himself and listen to us play. I thought maybe it was my imagination, but he seemed to show a lot of interest in my act.

One night he called a waiter and said to bring him half a dozen ham and egg sandwiches. The way Tait's made ham and egg sandwiches, one was a meal.

"You want halfa dozen sandwiches?"

"Yes."

"Well, that's what you'll get."

Was he astonished when the waiter lined them up! I couldn't help laughing, and he beckoned me over.

"That's not the way we serve them in Shanghai. We order one but it comes cut up in six pieces, so we say half a dozen. Son, sit down. Help me out on these. I'm like a native in a strange country.”

We talked. He told me his name was Louis Ladow and he was the owner of the Old Carlton Cafe in Shanghai. I didn't know it at the time, but the Carlton was world-famous among people who traveled. Mr. Ladow told me he had gone to China as a steward on a liner in the old days. He left the ship and went into business. He opened the Carlton Hotel in an old wooden building in the heart of the commercial district on Ningpo Road. To begin with it was a small restaurant downstairs with a few rooms on the second floor. Later he remodeled the upstairs into the Old Carlton.

“Look, son, I've been watching you work here. How would you like to come to Shanghai and work for me?"

Just like that. He proceeded to offer me a year's contract, complete with passage over and back. Just like that I said I'd take it. At the moment, for all I cared, they could turn Tait's and the Little Club into a coffee shop and restaurant any time they wanted. Whitey Smith was headed for China!

Smith arrived in Shanghai to great fanfare in 1922, and he remained in China until 1937 (though he took at least one trip back to the States during that period). During that period, he played with his jazz orchestra in many of the city’s finest ballrooms and nightclubs, including the Astor House, Majestic, and Paramount. He even tried to set up his own nightclub, the Cinderella, in 1932, but a war was on (the Sino-Japanese conflict in Zhabei), the timing was bad and the place went bust. When the Japanese military invaded China and took over Shanghai in 1937, he moved to Manila, where he was eventually incarcerated in a Japanese prison camp during the height of WWII. Upon his release, he remained for the rest of his life in Manila.

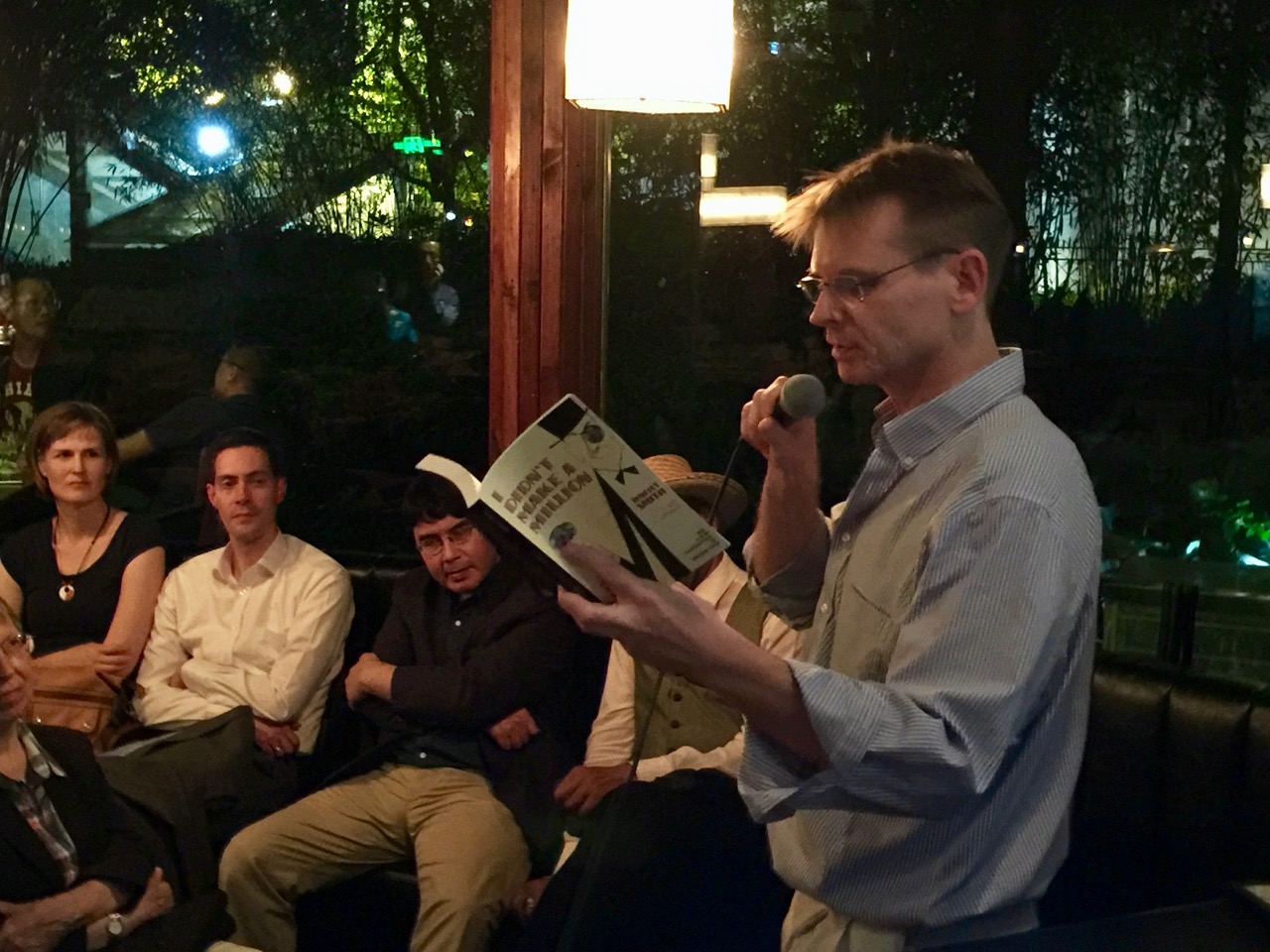

One of my favorite stories in Whitey’s book is how he taught China to dance. This is a story that I relate in Shanghai’s Dancing World and Shanghai Nightscapes, and also never tire of telling in my numerous talks on Shanghai’s jazz age. Here in Smith’s own words is the episode, which begins when Ladow’s Carlton Cafe closed down, and he and his orchestra began playing at the Majestic Hotel Ballroom. The story is recounted in Chapter 5 of his memoir. During our talk last night, I asked my friend Jim Scyszko, another man who taught China to dance (he started a swing dance movement in Shanghai many years ago), to read from this chapter, and he did a smash-up job.

Now I had problems. The New Carlton was gone and our jobs with it. I had a first class dance band on my hands and no money to pay salaries. But Providence was with me this time. Hongkong & Shanghai Hotels, Limited, controlled the top-level hotel business throughout China. They were a really big and stable outfit. When they offered me and my band a job playing in the Peacock Grill Room at the Astor House in Shanghai we didn't waste any time accepting it, we jumped at it.

I sent to the United States for six new American musicians and on November 20, 1923, fourteen months after I arrived in China, my new band and I opened with a bang and from that day on we played to capacity crowds.

But the Hongkong-Shanghai Hotels, like Mr. Ladow, were not satisfied and thought that they should have something bigger. So after careful consideration, they purchased the George McBain mansion which took in a full square block of Bubbling Well at the corner of Seymore Road. Poor Brother McBain practically had been camping out with only thirtyone suites. The setting was like paradise with beautiful elaborate Chinese gardens surrounding the mansion.

My band and I kept making music for large well-paying crowds at the Astor House while they turned the McBain mansion into a new hotel with a three-million-dollar ballroom big enough to accommodate eighteen hundred people. Mr. James Taggert, the managing director, hired a famous French architect to deign what turned out to be, I can say without fear of contradiction, the most elaborate and grandest dance pavilion anywhere.

When I went over to look at it I couldn't believe my eyes. I was absolutely flabbergasted! The ballroom was goldleaf and marble in the shape of a four-leaf clover with a huge fountain in the middle. There were two-inch Peking carpets covering the table area. Murals and ceilings were done by famous artists of Italy and France. Off to one side of the ballroom was the Empire Room where only royalty could enter. For cocktails before dinner they had the Winter Garden, with running waterfalls, artificial stars in the "sky" which sported a traveling moon.

My first reaction was that this place was also years ahead of its time. I felt that they were making the same mistake that Mr. Ladow made. Who was going to support this big layout? The foreigners in Shanghai and the tourist trade certainly were not enough to pay off even the investment. I told Mr. Taggert that without doubt he had the world's most beautiful ballroom, but if China didn't learn to dance and begin to patronize us, he had just buried three million dollars. Mr. Taggert told me with a quick parry and thrust that was my responsibility.

I didn't know exactly how I was going to do it, but I knew that I had to have more people with money to spend to fill the tables on our two-inch thick Peking carpet. Obviously, I had to draw in the rich Chinese.

To appeal to the Chinese mind I was sure that I had to have something different. They would not be satisfied, I believed, with just good danceable music. I had to have something bizarre with plenty of novelties, Some of the things I tried in that beautiful gold-plated, marble pillared ballroom bordered on heresy. They resembled the Disney fantasies. I had a miniature train built to run round, over and through the band stand and Mama Schmidt's son, Whitey, stood out in front of the band swinging a red lantern calling out the names of Chinese stations while my musicians rendered choo-choo effects in the background.

There was a number called Kitten on the Keys which I thought was good. We built a tremendous black cat and stuffed it with old rugs and placed it on our grand piano. Spring-driven motors made it move like a playful Siamese while my piano player made like a tom cat on the ivories.

Another month and a few Chinese began to drop in for a look-see, but, of course, they didn't dance since they didn't know how. At the same time I had to keep our International 400 happy because they were the people who were spending the money which paid the overhead. There was still a large deficit. I didn't know what else to do but I knew I couldn't give up. If I did, there was no place to go except down, and I'd been that way once already.

I had a friend, a general in the Chinese Army whom we called General William. He was a graduate of Notre Dame and a regular patron of the Majestic. Because of his American background, he liked our music. General William and I became intermission pals and I told him about my problem. The Chinese general had an answer.

"Whitey", he said, "your music is good and I enjoy it. From what you tell me, you are trying to bring more Chinese into the Majestic ballroom."

I told him that he was so right.

"If you are going to do that, you are going to have to play music that these people understand. The Chinese ear," he continued, "is educated only for melody. You must get that modern deep harmony out of your music and stay more with the melody." I began to see his point.

How we struggled! The melody was there in the stuff we had been playing, but it was buried under crazy accents and trick harmony and the Chinese couldn't find it, or remember it.

We scouted around and found the music to some old Chinese folk song melodies adaptable to band treatment. Chinese music is scaled high. It is repetitious and sing-song. To the American or European ear it sounds like a rising and falling wail from a torture chamber. It is punctuated with clashing cymbals.

A couple of the boys assisted by interpreters worked out arrangements based on Chinese music with – to them – familiar melodies. The saxes, trombones or flutes carried the tune, the only variation being by octaves. Sometimes the violin would take over. Guitars and traps were worked into the background, softly.

Jimmy Elder was our piano player, and a good one. Poor Jimmy. He tried hard to work the piano in somehow, but pianos just don't fit Chinese music. Nine trained fingers became useless. Only one was needed. It drove Jimmy nuts.

It was monotonous torture for all of us, but we stuck to it and more Chinese began to drift in. At first it was out of pure curiosity. Then they began to flock in for enjoyment.

Of course we didn't play Chinese music exclusively. We had to keep the International 400 happy too. We calmed down the Charleston and brought out the melody in it. We played Dardanella and the Missouri Waltz, Stumbling All Around, Somebody Loves Me, and Who. We alternated with our Chinese adaptations and gradually got something of a dance beat into them. The Duke of Kent, one night before a dinner party he was giving, brought me the music to five or six numbers which all became very popular.

The Chinese liked it and clamored for more. Before long they began to dance. They liked Singing in the Rain, Parade of the Wooden Soldiers, and the Doll Dance. Once in a while we would really let go with the St. Louis Blues and you could feel the younger Chinese begin to catch fire with it.

My friend General William was right. At Sunday afternoon dances, the Majestic ballroom began packing to capacity. eighteen hundred people. Many of the 400 were waiting on the outside to get in.

I shall always remember a compliment paid me by Pearl Buck, the famous writer who was herself an Old China Hand. She remarked to some of her friends that Whitey Smith had brought more good will to China than many an ambassador. He had taught China to dance. I give General William a great big hand for his timely assist on that one.

After I wrote a previous journal entry on Whitey Smith, I received this message: "My name is William Stewart my maternal grandmother's sister was married to Whitey Smith and lived in Shanghai in the 1920's I have original pictures of the band from this era." William kindly sent us these photos (above and below).

Whitey Smith’s band also composed and recorded their own original songs. In 1928, on the Victor Label, they released two double-sided records with four songs on them. The most well-known among them is “Nighttime in Old Shanghai”. Here are the lyrics, though one part has always stymied me. (If you take a listen and think you know what he’s singing, please let me know!) Graham Earnshaw performed the song during our event.

Nighttime in Old Shanghai

When it's night time in dear old Shanghai

And I'm dancing sweetheart with you

When it's bright time in dear old shanghai

With our lips all __________

In my arms dear

Away from home dear

We'll let the rest of the world go by

While the moon shines

Brightly we'll make love

When it's night time in old shanghai

The other three songs, "Chinese Wedding", "She Wonders Why", and "To a Wild Rose" are more obscure and unlike "Nighttime..." they have not been rereleased. However, I was delighted when Avril Moncrieff from Langport, Somerset in the UK, sent me a message to let me know that she has a copy of his record. She sent me these recordings, which I played during the talk last night. I have put them on youtube to share with the world:

Little Beat Records out of Denmark has posted materials on the biography and discography of Whitey Smith and his orchestra, which can be found on these links:

http://littlebeatrecords.dk/LittleBeatDK/Diskografier_files/Schmidt,%20Sven%20Eric%201928.pdf

I have posted on youtube a clip from British Fox Newsreel shot in 1929, showing Whitey Smith’s orchestra performing at the Majestic gardens while elegant Chinese dancers show off their skills. This clip never fails to delight audiences when I give talks on the subject of China’s jazz age:

And here's another that shows a closeup of Whitey and the band. Whitey mentions this film in his memoir, as well as the records he produced with his band in Shanghai:

The Fox Newsreel director, Mr. Bonny Powell, shot movies showing the Chinese dancing to the latest American music. In this picture I featured a song written by two members of my band, entitled, "When It's Night Time In Dear Old Shanghai And I Am Dancing, Sweetheart, With You." It sounds kind of corny now but I made a Victor record of it and we sold thousands to the Chinese. It was so successful, as a matter of fact, that it later became part of the Magic Carpet series.

My band made a record now and then for local companies too. Once in a while, I would even write a little tune and if it went over, I made a recording of it. I wrote one I called A Chinese Wedding, but I was stuck for a real Chinesey introduction. While in a department store one day I heard a Chinese girl singing accompanied by a Chinese fiddler. I asked the clerk what the song meant and he replied, "Man, wife, plenty trouble. Wallow! Wallow! Wallow!" That sounded like my answer so I asked the singer and accompanist to come to the studio to record.

After a thousand records had been released to the public I found through a friend of mine that the introduction I had worked so hard to get was really an old Jewish chant that the singer had picked up. So right away I had to recall my records, and palmed them off on the president of a local company who had just returned from the States. Within a month's time a sign in one of his record shop windows announced, “Buy one of our records and receive one of Whitey Smith's Free.”

My notes from the North China Herald shed some more light on these songs (also see my book Shanghai’s Dancing World, p. 47):

Whitey Smith and the Majestic Hotel Orchestra have produced four records on the Victor label; 10 musicians on 36 instruments, and Whitey and a Chinese young lady sing. Influenced by Chinese music. Records include “To a Wild Rose,” very danceable. “one merely glides into the steps of his partner and sentimentally forgets tariffs and brokers, Chinese politics and the cost of living.” Another record is “Night time in old Shanghai” “a delightful piece with a Chinese motif, the clamour of Nanking Road the dance at the Majestic and perhaps the fearful loneliness, the “blues” of the Bund.” “She Wonders Why,” a story of a Russian cabaret girl who wonders why the young man chose to dance with another partner. “The Chinese Wedding” with female song accompaniment (“Our Local Jazz Composer” in North China Herald, 1/23/1929)

Listening to "Wedding Song" in particular, you can begin to hear the sounds of the Chinese Jazz Age which came to fruition under Chinese composer Li Jinhui and others during the 1930s (see Andrew Jones, Yellow Music for a study of Li Jinhui, the "godfather" of Chinese pop music). This makes me wonder if Li Jinhui frequented the Majestic Ballroom during its heyday in the late 1920s and was influenced by Whitey Smith's "jazz music for Chinese ears."