(CAUTION: Reading can be habit-forming.)

Every year, I probably go through 50 or 60 books, and this number doesn’t count the books that I encounter in my various research projects. I’m talking about books that I read mainly for pleasure, enjoyment, and personal enlightenment. Many of the books that I pick up in a given year don’t get read in their entirety; there’s sort of a Darwinian whittling down to those books that truly urge me to go deeper and deeper into their pages. For example, this year I started in on two massive tomes on the life and times of Ludwig Van Beethoven, in honor of his 250th birthday. I wasn’t able to get through either of them, so perhaps they will be part of next year’s reading list.

The books that I’m listing here are ones that I did read in their entirety over the year 2020. These are books that I enjoyed thoroughly and by which I was educated, enlightened, and sometimes even mystified. These are books that captivated, entranced, and transported me into their specialized worlds. This was a special year of course. It was a year for indulging in escapist fantasy, and also a year for understanding better our history and environment and where our world is heading.

Because I spent six months of this past year in my home state of Massachusetts, this list also reflects my own interest in our local and regional history and the environment of the place where I grew up, and which I returned to for a spell after living most of my adult life abroad. Otherwise it’s a réflexion of my tastes and interests and my desire to escape the mundane world now and then.

Here are my top reads in the year 2020:

The Overstory, by Richard Powers (W. W. Norton & Company; Illustrated edition, April 2, 2019))

In January, I picked this book up by chance in the Kinokuniya Bookstore in Singapore. Little did I know that it would draw me deeply into the mysterious world of trees and forests over the next few months. I could not have predicted at the time that I would spend the next several months sheltering in my hometown of Acton, Massachusetts, and that I would be passing much of that time roaming the conservation lands and wildlife refuges of my home state. This novel tells the story of trees and forests from the perspectives of several characters, who, like the trees themselves, appear to stand on their own, but over the course of the book we find that their lives are intimately intertwined. The climax of the story appears to revolve around the struggle of a group of protagonists to save towering Pacific Redwoods from destruction and deforestation—at least, that is the most grippingly memorable part of the book. Meanwhile we are treated to a treatise on trees (oooh, that came out nicely) and learn a great deal about their lives and their connections with each other and with other members of the forest—which itself comes across over the course of the book as a living, breathing organism. A masterful work of prose and poetry, this book is an epic tragedy of how our human greed and lust for land and material wealth has shattered the natural world, which is far more finely, delicately, and magically wrought than anything human hands can construct.

A Long Petal of the Sea, by Isabel Allende (Ballantine Books, January 21, 2020)

This book was given to me as a gift by my aunt (in exchange I gave her my copy of The Understory). I hadn’t read Isabel Allende before, and I was in for a special treat. I love historical novels, and this one took me deep into a world with which I was only vaguely familiar if at all. The novel begins in Spain during the Spanish Civil War of the late 1930s. It then follows the story of two refugees from that conflict, Victor and Roser, as they make their way across the ocean to settle in Chile. It’s both a love story over a long span of time, and a story of war, exile, displacement, identity, and revolution. Reading this story puts our own rather mundane lives into perspective against the grand backdrop of the twentieth century with its wars and revolutions. The two main characters are models of fortitude, endurance, patience, and humility. This was a good book with which to settle into the pandemic and accept the fate of our current moment in time.

The Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula K. Leguin (HMH Books for Young Readers; Reissue edition, September 11, 2012)

I remember reading this series when I was a child of around ten. In February of this year, while we were “escaping” China and sheltering in the USA, I read this book to my younger daughter Hannah who was also ten at the time. (This will probably be the last book that I have read to my daughter since she seems to have grown out of having Dad read to her. In fact, much of the book she read to me.) This is a masterpiece of literature, and I suppose I didn’t appreciate that until now. It is a tale of a young wizard named Ged who lives in a medieval fantasy world, a seafaring world composed of islands. After using his powers to successfully deflect an invasion of his home mountain village, the boy is apprenticed to an older wizard named Ogion, who teaches him a thing or two about the craft and warns him of its dangers. Then he is sent across the sea to a school of Wizardry for further instruction. This ain’t no Hogwarts, mind you, and Ged ain’t no Harry Potter. While in school, Ged is provoked by a rival to conjure up a mysterious and deadly power, which then hunts him across the world—until he realizes that it is he who is the hunter. An incredible fantasy novel and a masterwork of fine literature, this should be required reading for all ten-year-olds who love fantasy fiction, and for their parents as well.

The Once and Future King, by T. H. White (Ace Books; Reprint edition, June 1, 1987)

I was hoping that this would be the next book on our fantasy reading list, but Hannah quickly grew out of having her Dad read to her. (She is a voracious reader on her own, and far from it for her Dad to stand in her way.) Thus, I picked up this book and started reading it for myself. I’d always wanted to read it ever since I was her age or a bit older, but I had never got around to it. Thus, it was with great pleasure and delight that I discovered what a wonderful book this is, whether for a ten-year-old or a fifty-year-old. This is a high fantasy novel based upon the medieval legends of King Arthur and his court. It begins as young Arthur known as “Wart” gets schooled by an aged sorcerer named Merlin. The mage transforms the lad into various creatures, including birds, fish, and at one point, an ant, so that he may learn different viewpoints and study the ways of nature. These are fantastic depictions about what life might be like from the perspective of other beings and creatures. One of my favorite scenes is Wart’s conversation in the moat as a small fish with a very large and menacing pike, who is trying hard not to eat him but cannot control his appetite. This is reminiscent of the great Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi who once dreamed of being a butterfly. As the story progresses (it is actually several books in one package), Arthur becomes a man and a king. The two other main characters in the story are his leading knight Sir Lancelot, and Arthur’s wife Guinevere. Of course the story focuses on the infamous romance between Lancelot and Guinevere over a long period of time and Arthur’s denial of that romance and its ultimate tragic consequences. Another masterpiece of modern literature, this novel or series of novels throws one into a medieval world of jousting and heraldry with its antiquated yet still recognizable value system of chivalry. It’s also packed full of dry wit and humor, and like the Star Wars series or Shakespearean dramas it has numerous characters who provide for comic relief throughout what is otherwise a very serious and tragic tale of war, conquest, rivalries, and rescues.

Leviathan Wakes, by James Corey (Orbit; Reprint Ed. Edition, June 15, 2011)

Okay, I admit to sneaking this book in as well as part of my fantasy/sci-fi binge after the pandemic hit us with its first wave in spring and left us stranded in Acton Mass. It started with me watching the series called The Expanse on Amazon Prime, starting bass-ackwards with season 4, which hooked me into its gravitational pull, then on to seasons 1, 2, and 3 (I’m watching season 5 now). The idea of kicking ass in space intrigued me, and the visuals and special effects are phenomenal. After binge-watching the series, which involves various groups of humans, divided roughly into “inners” and “belters” fighting each other while dealing with a mysterious “protomolecule” that shows up in the solar system only to wreak havoc on humanity. I stayed up late nights reading this book, or else read it in the middle of the night when I was trying to get back to sleep. Soon, the saga of a crew of intrepid spacefarers caught up in various inter-solar system intrigues crept into my subconscious mind and started invading my dreams, leaving me stranded deep in space. It isn’t high literature, not by a long shot, but it was awesome escapist fantasy and sci-fi (and it kicked ass too!).

The Hidden Life of Trees, by Peter Wohlleben (Greystone Books; Illustrated edition, September 13, 2016)

After reading The Overstory, and in the midst of being drawn into the magical and mystical world of forests in and around my hometown of Acton, Mass., I devoured this book. Written by a German forestry expert, the book is divided into dozens of small chapters, each of which describes a facet of what we know or may conjecture about the lives of trees. We learn that trees are intimately connected through their root systems and through the vast networks of fungi that live underground, otherwise known as the Wood Wide Web. We also find out that trees nurture and take care of their siblings and children, and that they live in a precarious balance with each other as they search for space and light in the limited canopy of the forest. We discover why some trees dominate that canopy while others fall to the wayside, never to grow into full being. We study how trees conserve and expend their resources and energy, and their various strategies and methods for doing so, as well as their altruism vis-à-vis other trees. And so much more. If you are into trees and forests, this is essential reading.

Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England, by Tom Wessels (Countryman Press; 1st edition, September 20, 2005)

Facebook is good for some things, among them suggestions for reading. Early in the year, after I posted messages about reading The Overstory and my excursions into the woods of New England, a Facebook friend recommended that I read this book. Sure enough, it was a marvelous guide to our local forests. The author uses forensic analysis to enlighten readers on how to “read” the forested landscape and learn from various clues about its development over time. He teaches the reader how to tell how old the forest is and when it was demolished and restored. The book begins with an account of the forests under the stewardship of the original inhabitants of the land, who burned off the underbrush to keep it from getting too cluttered. Then he moves on to discuss how the first settlers from the Old World changed the land to make way for their farmlands and homesteads, cutting down countless forest in the process, and building the low stone walls that still line the forests of New England today. After local farms gave way to the larger more efficient farms of the American heartland connected by canals and railroads to the eastern seaboard, the lands and hills of New England became pastures for sheep and cows until the wool and dairy industries also went bust. Since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these New England forests have regrown themselves and they are now carefully stewarded and protected by conservationists and environmentalists. Today, over 60 percent of Massachusetts is forested land, which really is miraculous given how bare the land was a century ago. As Mencius once said, just because the mountain is bare, doesn’t mean the sprouts aren’t there. And just as human virtues may do so, so too the forests that we decimate may, given the opportunity, regrow and regenerate over time.

This Land is Our Land: The Struggle for a New Commonwealth, by Jedediah Purdy (Princeton University Press, September 17, 2019)

One of my Duke colleagues recommended this book by a former Duke professor of law and an expert on environmental matters. This is a sobering book about our Commonwealth (in particular, but not exclusively the United States) and how we’ve messed it up over the past few centuries with our individual and collective greed, our wasteful industries and our rampant deforestations, and how we can regenerate it if we try. It makes one far more aware of the human impact on our planet, reminding us continually of how much infrastructure we build to sustain our ways of life, and our destructive impact on the natural world. The author also connects environmental issues with social justice issues—a theme that was especially prevalent in the USA over the past year. Whether mining for coal or industrial farming for pork, and whether planting cotton or tobacco, humans are changing and decimating our natural landscapes in ways that will impact our world for centuries to come. An important read for our times.

Ceremonial Time: Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile, by John Hanson Mitchell (Counterpoint; 1st edition, March 4, 1997)

This was another recommendation from a Facebook friend. Written by a locally based author and naturalist, the book is a natural and social history of the area around my hometown in Eastern Massachusetts. It is predicated on the mystical notion that time is an illusion. The author blends historical lore and native tales with his own observations of how the land and the environment of our Nashoba Valley area has changed over the past several millennia, starting with the recession of the great glaciers that once covered this region with snow and ice, and ending in the 1970s with the rise of the tech industry. I found this to be an amazing journey into local history and have since recommended it to all of my fellow Actonians, but anybody interested in local, regional, and natural history would find it of great interest. Mitchell is an engaging and perceptive writer, and he recounts in fine and often hilarious detail his interactions with local inhabitants, both human and otherwise. He lives in the neighboring town of Littleton on the border of Westford in a land he calls Scratch Flat, an old name for this drumlin-filled farmland. Trained as an observer and writer of nature, he is at his best when describing the flora and fauna and the natural systems that course and flow through the region. This book inspired me to take my family on a few jaunts over to Beaver Brook, the waterway he describes in such loving detail in his book. Given that my aunt and uncle have lived in that area since the 1970s, the book opened me up to new vistas and perspectives on a land I thought I knew well, but hardly knew at all.

Walking Towards Walden: A Pilgrimage in Search of Place by John Hanson Mitchell (Counterpoint, March 11, 1997)

I was so taken by Mitchell’s book that I ordered several others. My next read in the Mitchell local history series was this one. The book is also a natural and social-political history of the region, but this time framed around a single hike he and his friends took through the “wilderness” of the region from Westford to Concord. During their hike, the trio of friends made their way through forests and across brooks as much as they could until they reached the fabled Old North Bridge, the legendary starting point of the American Revolution in April 1775. The book is full of anecdotes about that legendary battle and about other battles such as those of the so-called King Philip’s War, which pitted native inhabitants against the colonial settlers in the late 1600s. It is also chock-full of observations about local people and about the critters that inhabits these forests, fields, and farmlands. I was happy to read a book whose every page contains loving descriptions of roads, pathways, forests, and fields with which I myself am intimately familiar, and which I became even more familiar with over my six-month sojourn in Acton Mass. As suggested by its title, the book also contains numerous references to Henry David Thoreau and his pal Ralph Waldo Emerson and their peregrinations through this hallowed land in the mid-19th century.

Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls by Robert Thorson (Bloomsbury USA; Reprint edition, March 1, 2004)

Continuing along the theme of local, regional, and natural history, over the course of my six-month stay in Massachusetts, I became more and more fascinated not only by the forests that are so well preserved now, but also by the low stone walls that criss-cross these forests. I’d grown up in New England, so I was familiar with these walls of stone, but I knew very little about them, other than that they’d been put up by colonial settlers centuries before, perhaps to demarcate their land. This was only partly true as I learned this past year. This book provides a very detailed historical account of the stone wall-building projects started by the colonials and continued by the American farmers in New England up until the 19th century. It starts by going back millions of years to study the formation of the rocky land and takes that story all the way to the glacial epoch of fifteen or twenty thousand years ago, when these stones were lifted, carried hundreds and thousands of miles and deposited in the soil like seeds. Since then, the stones have been brought up to the surface through natural forces such as frost heaves and more recently through the tilling of the soil. When the first settlers arrived in the New England area from the Old World, they began the project of removing these stones from the fields and farmlands and homesteads they were building and cultivating. Each year they had a new harvest of stones to deal with, and so these wall-building projects lasted for several generations. One remarkable thing about the land in New England is that it is similar in so many ways to that of Old England, and so these farmers and settlers knew exactly what to do: use the stones to build makeshift walls and “fences” to demarcate their land, which served two purposes: to rid the soil of the stones, which got in the way of the farming and pasturing, but also to mark out their territories. All this was done much to the perplexity and chagrin of the native inhabitants, who had a very different relationship to the land and did not bother moving heavy stones around (whether they used stones for ceremonial purposes is another matter, but certainly they did not have the time or leisure to build stone walls, nor any reason for doing so). By the late nineteenth century if not earlier in places, this practice largely was discontinued, but it has left a distinctive mark on the New England landscape that will last for centuries if not millennia to come.

My Heritage with Morning Glories, by Tania Manooiloff Cosman (Creative Communication Services; 1st Edition, January 1, 1995)

Last spring, a colleague of mine who collects old memorabilia and archival materials on foreigners and their lives in treaty port-era China (among other things) mentioned this book to me. I bought a copy of the book and read it with great delight. For decades now, I have been fascinated with the stories of the Russian refugees, who made their way to China after their country underwent the great revolution that brought the Communists to power and the Soviet Union into being. I’d read many histories and articles on the Russians in Shanghai and elsewhere, but I had never read an actual memoir by a Russian refugee who grew up in China. This is a sad, yet ultimately triumphal story, of a Russian girl born and raised in Manchuria, who comes of age in Harbin and then in Peking in the 1920s-1930s. After suffering the loss of her parents at a very young age, she is brought up in an orphanage in the Russian-filled town of Harbin, where she receives a basic education and begins to learn English. As a young woman, she finds her way to Peking (Beijing), where she ends up working in a cabaret (this is what interested me in the first place as it intersects with my own research on nightlife in 1930s Shanghai). Eventually she finds solace and safety with one of our great Sinologists, the American Ida Pruitt, who was living in Peking at the time. That encounter brought her eventually to settle in the United States, where decades later she wrote this unique memoir of her life in China.

Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai, by James Carter(W. W. Norton & Company; 1st edition, June 16, 2020)

Occasionally, a colleague of mine in the China studies or Shanghai studies field writes a book that reaches a wider audience than the typical academic monograph. This is definitely the case with this book, which my fellow China historian James Carter wrote for a broader public. Published by a trade press, the book is designed for readers who may or may not have any prior background in the history of modern China and of treaty port Shanghai. It provides enough background info to keep general readers in the loop, while also serving the interests of specialist readers such as myself. The book focuses on the story of the Shanghai race club and the horse races that were the centerpoint of social and cultural life in the city during the early twentieth century. It leads inexorably up to the early 1940s, when the city was taken over by the Japanese who were fighting a protracted and undeclared war in China. This is history of British, western, and Japanese colonialism and imperialism and of Chinese state-building and resistance, masked as a fun day at the races. We learn about the lives and fortunes of many of the prominent citizens of Shanghai, who collectively built its industries and financed its various pleasures. This is a history book that is filled with fascinating characters and stories, and one that I recommend to anybody interested in modern China or in Shanghai’s own unique history.

Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, by Joshua M. Greene (Wiley; 1st edition, June 1, 2007)

Anybody who follows my blogsite knows that I am a fan of the Beatles. In addition to listening to their music, I’ve been reading Beatles literature ever since I was a strapping young lad. But as everyone also knows, or should know by now, after they broke up circa 1970, each member of the Fab Four went his own way. While Ringo seems to have largely faded into a pleasant semi-retirement over the decades, popping out on occasion to support other band members, the other three men carved out their own post-Beatles musical careers. John’s tragic murder in 1980 put an early end to his career as a post-Beatle, but George and Paul soldiered on to the end of their lives. Paul just released his 18th solo album--and the man is turning 80 soon! George didn’t make it that long; his life ended in 2001 when he was in his late 50s, but during his solo career spanning several decades, he too put out many albums. Some of these were duds, but some are now classics, starting with his multi-album collection All Things Must Pass, which he produced just after the Beatles broke up. In 1987, he released his album Cloud Nine, which I absolutely adored. Just after he died, his son Dhani produced his posthumous final album Brainwashed, which may just be the best of the bunch. Certainly it concentrates his finest energies and song-writing talents together into a final statement about George as a solo artist. Obviously by now, you know that I’m a fan of George Harrison the musician. This year, I discovered this book, which is a biography, but also a deep dive into the spiritual world that George Harrison came to inhabit both during and after his stint as a Beatle. It sheds valuable light on his inner world and on his relationships with his various mentors, including the India musician Ravi Shankar and the spiritual leader Phrabhupada, as well as his friendships with followers of the Hindu sect known as Hare Krishna. Far from being batty fringe lunatics that as they are often portrayed by the media, these folks come across in the book as some of the most pleasant, delightful, and enlightened beings one could ever hope to meet. What emerges from this book is George’s deep and enduring spiritual faith and humanity, which informed all of his songs and albums in various ways and which sustained him until his rather premature death in 2001. In addition to Indian mysticism, George also steeped himself in ancient Chinese mystical thinking as well. As a professor, who teaches Ancient Chinese History and Thought, I was surprised and delighted to learn that two of his stellar contributions to the Beatles canon, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and “The Inner Light” were influenced by the ancient Chinese classics Yi Jing and Dao De Jing.

How Music Works, by David Byrne (Crown; Illustrated edition, May 2, 2017)

I have been a fan of the music and performances of David Byrne and the band Talking Heads since the early 1980s, when I was coming of age and my own musical tastes were forming (not a deep fan mind you—I haven’t kept up with his work so much since the 1980s). Upon the recommendation of a friend who is also into analyzing and writing about music scenes, I downloaded the Kindle version of this book. It is rare that a musician and performer can provide us with such a comprehensive analysis of the world of music of which he or she plays a part. Byrne is one of those rarities. Talking Heads was an artsy rock band that emerged in the late 1970s out of the low-fi scene fostered by the now famous live house CBGB in lower Manhattan. After gaining popularity for their recorded music in the early 1980s, they took on bigger stages and Byrne was the subject of at least one film. Now he is regaining his fame in the wake of the successful musical American Utopia. The band was known for its danceable rhythms and for David Byrne’s frantic stage performance and sartorial flare. One of the themes Byrne develops throughout the book—something that would seem obvious but is often overlooked in analyses of music—is the importance of dance and its intimate relationship to music. The other theme is space. He is a keen analyst of the spaces and contexts in which music is performed, and the book is full of sketches of musical spaces including the famed CBGB, which underwent a renovation in the 1980s. As a scholar who has spent a lot of time in live houses and dance clubs and has analyzed the spaces of these clubs, I commiserate deeply with this point of view. Space is often overlooked—in fact, physicality of any sort tends to get overlooked in musical studies which tend to focus on the musical product itself. Perhaps this is a product of the advent of recording technology in the 20th century, which tends to abstract the music from physical space—a subject that the author covers in great detail and from personal experience as well as historical analysis. Byrne is also very careful in setting the stage for his performances, and what sort of equipment to use and what kind and color of clothing to wear in order to put the attention on the performers. This is a book that is worth reading more than once, and it will likely become part of my own canon of musical reference books.

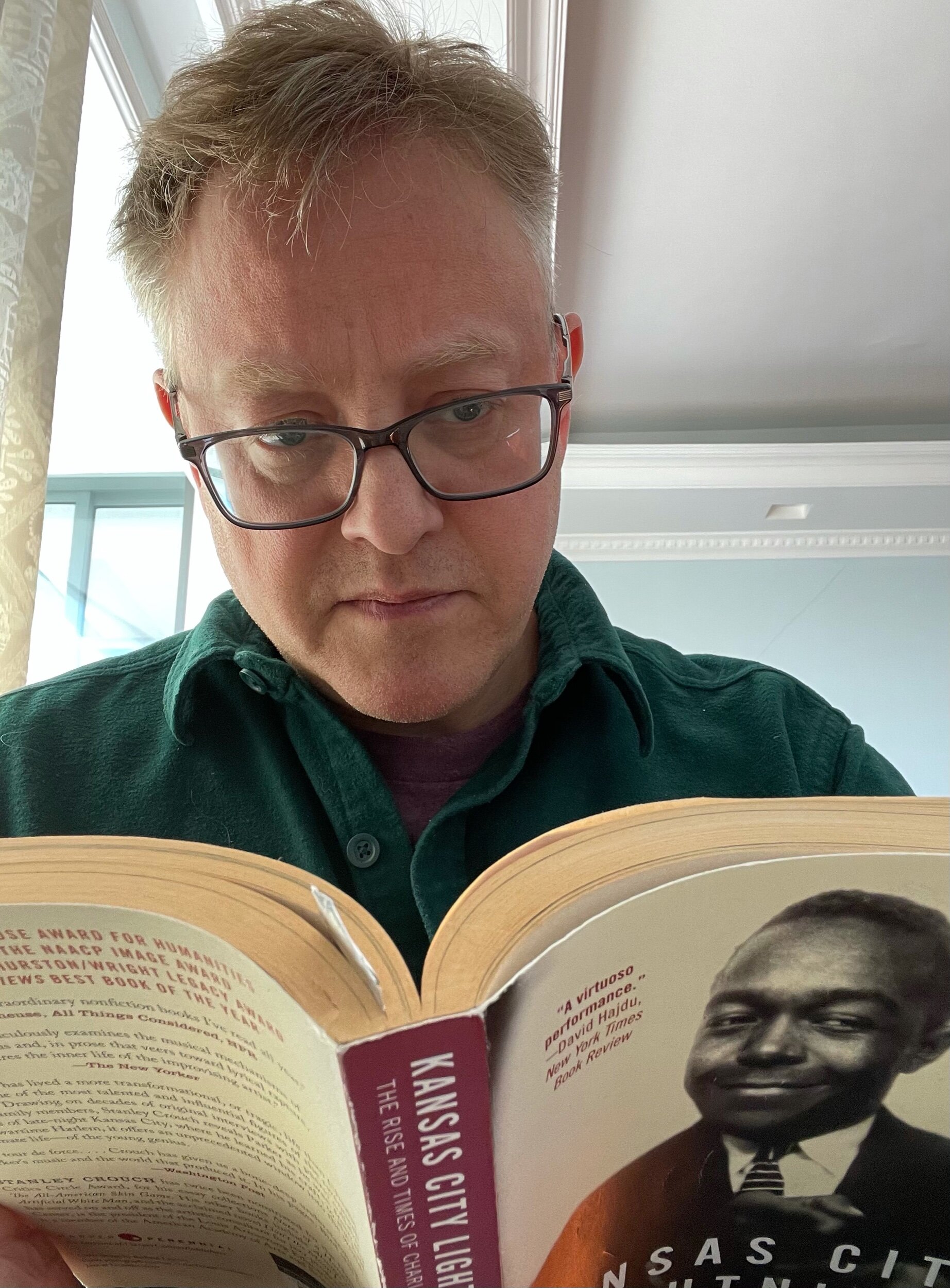

Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker, by Stanley Crouch (Harper Perennial; Illustrated edition, October 21, 2014)

Although I haven’t quite finished it yet, I thought this book worthy of inclusion in my 2020 list. Sadly, the author passed away this past year. I found this book on the shelves of the Concord Bookshop, where I do my book shopping when I’m back in my hometown. Even though it’s basically a work of non-fiction, it reads like a novel. The author Stanley Crouch is a well-known expert on jazz history, who appears in Ken Burns’s epic doc series, Jazz. He is also a master of prose, and the book is a winning combination of story-telling and analysis of what goes into the making of jazz music. Charlie Parker is one of the legendary figures in jazz history, having risen up from obscurity in the 1930s Kansas City scene to become one of the founders of the Bebop movement in the 1940s, only to succumb eventually to illness abetted by his long-time heroin habit. Those who know jazz know the basic outlines of the story, but Crouch takes us deep into his interior world as well as tracing the pathway through which he achieved his greatness. We find out about the not-so-legendary figures who served as his guides and mentors along the way, such as Buster Smith, whom they called The Professor for his erudition and finely honed musical skills. We also are thrown into the scenes that he inhabited, such as the rollicking Kansas City nightlife scene, or the various gigs he served while on the road learning his craft. Like I said, this review is a bit premature since I’m only more than halfway through the story and we haven’t even gotten to the part yet where Parker, or Bird as they called him, rises to his legendary status and launches the Bebop movement on the jazz world. So perhaps I’ll follow up with a more lengthy review when I’m done with the book, but suffice it to say that I’m learning a great deal about how jazz artists developed their individual and collective talents during this crucial time period in the history of this musical genre.

Modern Japanese Short Stories: Twenty-Five Stories by Japan’s Leading Writers, by Ivan Morris et al (Tuttle Press, 1962; republished in 2019 with a foreword by Seiji Lippit)

This is a brilliant and stunning collection of short stories from the early 20th century, featuring some well-known writers and some lesser-known ones (at least, today). I picked this book up at Kinokuniya Bookstore in Singapore last January when I bought The Overstory, so I suppose it’s fitting that I finish the list with this one. I didn’t take it with me to the USA, so it was waiting patiently on my bookshelf for my return to Shanghai. When I returned in September, we had to go through the mandatory two-week quarantine period. Fortunately, we were able to do most of that time in our own apartment (others weren’t so lucky and had to hole up in a hotel room for two weeks). As part of my daily ritual, each day I read one of the short stories in this book, and soon I was absorbed in the daily lives and rituals of Japanese people living in interwar and wartime Japan. I’ve been a fan of Japanese literature since graduate school when I started learning Japanese. Regrettably, I never took a course on Japanese literature at Columbia University back when Donald Keene was the reigning daimyo of Japanese literature, but I certainly did meet him as well as the other deans of modern Japanese lit. I did study Japanese history though, and that was one of my subjects going into my oral exams, the final stage before writing the doctoral dissertation. While researching the nightlife of Tokyo for a course I used to teach on Global Nightlife, I got into the literature of interwar Japan, and discovered Nagai Kafu. I also familiarized myself with the writings of Junichiro Tanizaki, particularly his novel Naomi, a Nabokov-esque novel about a man who falls in love with a young woman—a girl really—who works as a café waitress in Tokyo. These authors are both represented in this book, as well as many others with whom I’m less familiar. The stories range in subject matter and style from family tales to stories of relationships and exotic sexual encounters, and there are also several stories about workaday life. We meet people working in factories and on farms, and we spend time in a police station as they deal with some routine and some not-so-routine cases. The stories are arranged in roughly chronological order and they take the reader from the late Meiji Era to the post-war era when Japan was recovering from the bombings of the 1940s. For anybody interested in modern Japanese literature, history, and culture, I’d say this would be a very welcome addition to your library.