Chen Gongbo, taken when he was Mayor of Shanghai in 1943 (source: Wikipedia)

As readers of this blog and my book know, I have dedicated a good part of my career to resurrecting the ghosts of Old Shanghai. I'm a grave digger of sorts, an archeologist of urban history, whose job is to recover and reconstruct stories and times that have passed into collective oblivion. One story that I have chosen to focus on in future research is the tale of 陳公博 Chen Gongbo. Anybody who knows Republican Era history well ought to be familiar with this ghost of Shanghai's past. Chen Gongbo started his political career as a founding member of the CCP and was at the First Congress honored by the museum located ironically in the heart of Xintiandi, the city's leading entertainment and nightlife complex. Who better to embrace this contradiction than Chen Gongbo himself? Patriot, playboy, poet, romantic, revolutionary, and ultimately arch traitor, Chen personally embodied the many contradictory and conflicting impulses of Republican Era China.

After this historic first meeting that launched the Party that would revolutionize China, Chen traveled to the USA in the early 1920s, where he studied economics at my alma mater, Columbia. There he renounced Communism, returned to his motherland and embarked on a stellar career as a leading officer of the Guomindang. Chen became a loyal follower of Wang Jingwei, one of the stars of the GMD pantheon, whose ambitions to lead the party were thwarted by the coup by Chiang Kai-shek in 1926. During the 1930s, like Icarus, Wang soared too close to the sun--the Rising Sun that is--serving as foreign minister of the GMD he forged close relations with the Japanese and became the country's leading hanjian 漢奸 (traitor) after he chose to serve as the President of Japan's puppet regime in China during the war years. He died in 1944 however before the war came to a close. Chen on the other hand lived to meet justice at the hands of his former boss, Chiang Kai-shek.

Chen had a stint in the 1930s as the GMD's economic minister, where he helped to set China on a path of modernization that would carry the country into the 21st century as an economic colossus. When his mentor Wang joined the Dark Side, Chen at first refused to follow him. For three years, Wang begged Chen to come to his aid. Finally, out of sheer loyalty to the man who had nurtured his political career (or so I have heard--this is still a matter of future research and analysis) Chen joined him and became Shanghai's mayor in the early 1940s, when the Japanese military occupied the city.

While researching my dissertation and first book, I came across many references to the intriguing figure of Chen Gongbo, including a poem which I translate in my book Shanghai's Dancing World. The poem described a scene at a dance hall in Shanghai, hence the relevance to my book. Here it is in its original form and in my translation:

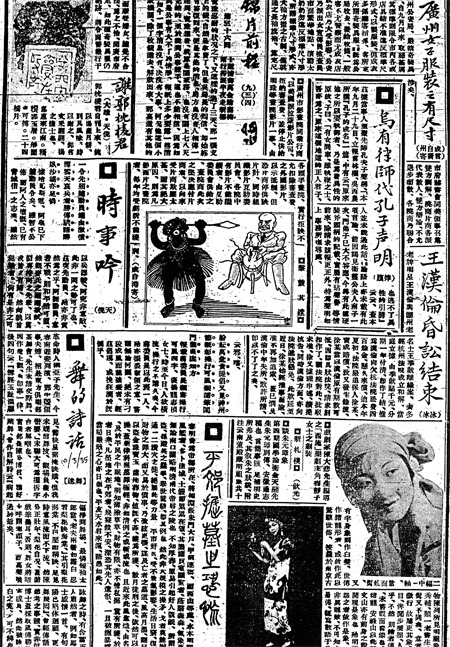

Here is the page of the newspaper, The Crystal (晶報) October 3 1935 issue in which Chen Gongbo's poem appeared. At the time he was an economic minister of the GMD in Nanjing. Below is a close-up of the article featuring Chen's poem and some others written about Shanghai's cabaret culture.

病起偏掙到舞場,

最憐短袖太郎當,

老夫兩鬢如霜白,

忍看梨花映海棠

(Sick and infirm, I struggle over to the cabaret,

Most pitiful are my short sleeves, too carefree,

An old man with temples that are frosty white,

I watch the pear blossoms shimmering on the ocean.)

It seems that Mayor Chen was still sowing some wild oats while in office. He was certainly familiar enough with the world of Shanghai cabarets and their lovely hostesses. But he was a family man as well, who raised a son in a large mansion where he kept his two concubines, a pair of sisters.

On the other hand, documents from the Shanghai Municipal Archives and some newspaper accounts from the 1940s seemed to suggest that Chen was dedicating himself to cleaning up the city, a long-term goal of the GMD that had been stymied by the shady alliance with the city's notorious criminal syndicate known as the Green Gang, and later by the Japanese occupation. In any case, Chen struck me as a very intriguing character. When I found out years later that my colleague and fellow Columbia grad student Margherita Zanasi had written an article about Chen Gongbo*, I wrote to her asking if anybody had written a biography of this man. She connected me to his living son, Kan Chen, a retired engineer living in California. I eventually met Kan in his home in the Bay Area and he gave me a set of original documents from his father's collection, urging me to write about his dad from an angle that had not been approached yet: poetry.

I also made the acquaintance of his grandson Jeff Chen, a high-powered lawyer based in Hong Kong, who straddles China and the West like a Colossus in the legal world. The other night, Jeff and I met for dinner, after which he gave me a tour of his grandfather's house on the corner of Donghu Road and Huaihai Road. The stately multi-roomed mansion that once housed Jeff's granddad and his concubines, and where his father Kan lived, is now being used (underused in our opinion) as a fancy seafood restaurant. The following night I took Jeff to one of my favorite jazz and blues bars in town, the House of Blues and Jazz. Comparing Jeff's photo with that of his granddad, one does note a distinct family resemblance.

Andrew and Jeff Chen in Shanghai's House of Blues and Jazz, May 13 2011

In 1946, after seeking refuge in Japan, Chen Gongbo was brought back by the US Military to China upon the request of Chiang Kai-shek. Many other collaborators were left in their high positions to keep the government of GMD-occupied China running, a fact that the CCP used to their great advantage in their anti-GMD propaganda campaigns. Chen had taken Wang Jingwei's spot as President of the puppet Republic after Wang died in 1944. If being the Mayor of Occupied Shanghai weren't bad enough, certainly Chen's position as Japan's top dog in China was a suicide pact and a startling fall from grace in his otherwise stellar political career as a Chinese patriot. Though his son Kan did his best to try and convince Chiang that his father deserved better treatment, Chiang was adamant. Chen was incarcerated for a spell in a prison in Suzhou, where he apparently befriended most of the guards, who were reluctant to see him shot. Before facing the firing squad, Chen Gongbo wrote a lengthy letter arguing for his exoneration, or at least explaining his life decisions. To this date, the letter hasn't been translated into English. I'm hoping to be the first to do so. Whether this will lead to an article about Chen and his fall from grace or a full-length book about the twists and turns of his life is yet to be determined and the product of many other factors in my own life and career, but surely Chen's story deserves more attention than it has been given by Western academia, and I'm hoping that I can find the time and the resources to devote to resurrecting this ghost that once loomed so large over Old Shanghai.

*Margherita Zanasi, "Chen Gongbo and the Construction of a Modern Nation in 1930s China," in Timothy Brook and Andre Schmid, eds.; Nation Work: Asian Elites and National Identities (University of Michigan Press, 2000)