Like most metropolises, Shanghai is a city of contrasts. Yet the contrasts here are steeper than in many other developed cities. Back in the 1930s, a young literary star named Mu Shiying described the city as "a heaven built on a hell" (see my translation of his famous "Shanghai Fox-trot" for the full story). While the Mao years of the 1950s-1970s had a leveling effect on the city's population, the Deng years and after have once again seen the rising rift between the haves and the have-nots. Wealth and poverty are often seen hanging out together in the modern capitalist metropolis, but Shanghai's own twists and tangles have created some amazing juxtapositions, making the city a concrete kaleidoscope of power and privilege, with towering glass spires and luxurious nightclubs and restaurants on the one hand, and old disappearing neighborhoods of brick or wooden rowhouses on the other.

Over the years we who live here have seen the steady disappearance of the poorer housing developments as they are obliterated to make way for the new fleet of high-rises. The most stunning example of this is the development zone chosen by Hong Kong real estate mogul Vincent Loh and his Shui On (Ruian) Company. The only remnant of what was once a tangled warren of longtang housing is the Xintiandi leisure zone. Its elegant townhouses, painstakingly reconstructed brick by brick by the office of Ben Wood and associates, never fail to attract swarms of foreign and Chinese tourists who love to sit at the outdoor cafes and watch the other tourists flock by. Where once hung strings of laundry like flocks of colored flags, and where wisened residents once gathered to gossip in decades-old networks of friendship, rivalry, and sociability, now crowds of strangers can sit and sip their lattes and their mojitos as they watch the parade of people flowing past their tables.

Ironically, this neighborhood was preserved because it was the site of the first meeting of the Communist Party in 1921, at an old schoolhouse that now functions as a revolutionary museum. There one can see Chairman Mao standing proudly above his revolutionary comrades as they plot the course of China for decades to come. Not that Mao was really there--he was conveniently airbrushed into this signal event in later decades by a Party that has proven all too willing to create its own special version of History--not that this is too much different from the USA for example, with our famous image of the Founding Fathers all prim and proper gathering together to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

The museum at Xintiandi is a good place to start thinking about how important this district of Shanghai was to the revolutionary politics of the age. For the past few years I have been developing walking tours of the so-called "Heart of the French Concession" and every time I take a group on a tour of that section of town, there's always some new information to pick up and digest. Nearly everyone who was anyone was living in that area between the 1920s and 1930s. People who dwelt in the longtang neighborhoods, townhouses, and mansions of the neighborhoods surrounding the old French Park (now Fuxing Gong Yuan) included many a famous Chinese writer, politician, general, actor, industrialist, and statesman. Someday soon I intend to write an article about the importance of this section of town to the making of modern Chinese history.

The other day I had the pleasure to lead a tour of the Heart of the French Concession for a group of around 40 people who comprised the German-Chinese Graduate School of Global Politics in Shanghai. I was expecting a group of Germans and was surprised when the great majority of students in the group were PRC Chinese. I had not given a tour of the Concession to a Chinese audience before. Would they be as interested in the history of this quarter?

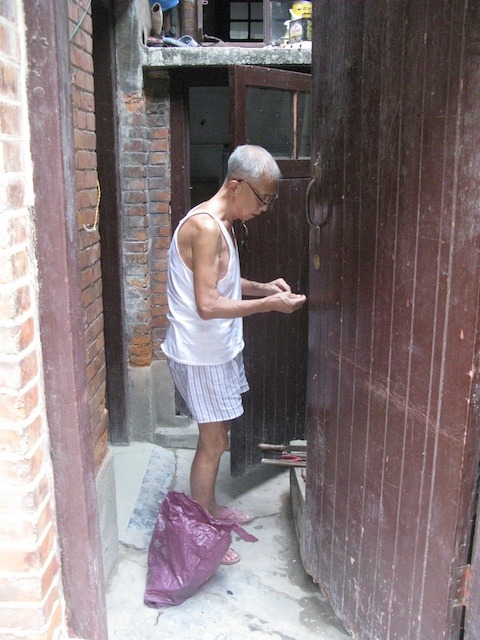

After giving a talk about Old Shanghai to the group at the Sambal Cafe in the Jiashan Market (a relatively new development of offices, cafes, and restaurants nestled in an alleyway off of Shaanxi Nan Lu), we ventured out, passing the wet market and headed across the street to the Cité Bourgogne, one of Shanghai's most impressive longtang compounds. Both entranceways into this rowhouse block boast gateways appropriated from the style of an old Chinese temple or palace. They are definitely the most glorious gateways into a longtang residential area that I have seen. Once inside I told them about the importance of these rowhouse living quarters to Shanghai lifestyles over the past century. We walked through the southern entrance and headed north on the main spine of the fishbone-like structure of alleyways, passing by this resident who had found a unique way to snatch a snooze.

We turned left and on the way to the western gateway we passed by an open door occupied by a white-haired fellow. I asked him how many people lived in this compound and he told us that there were 300 families, but that many out-of-towners had moved in and it was hard to gauge the real number of people living there. Seeing that he had a captive and partly female Chinese audience, he then began to boast about how he had been to Qinghua University in Beijing once to participate in a competition. He then started talking about tanks and how the Chinese had built the best one, and continued to parlay on until I decided that we had to get moving, but obviously our Chinese students who come from many different provinces were happy to get a chance to engage with a local resident.

Marching out of the grand gateway, we headed north on Shaanxi Nan Lu, passing the newly built theater on the grounds that once held the Canidrome race track, a popular greyhound racing venue in the 1930s run by Green Gang members, and the Canidrome Hotel, where one of the city's finest ballrooms operated. We then walked around an old luxury apartment building built in 1924 and passed through back alleys to our next destination, the King Albert Apartments. Among the group of students, one young woman named Jiang Wei was constantly at my side asking questions and making remarks about the neighborhoods. It was great fun to be with a Chinese group for a change--for one thing, I didn't have to translate for anybody we met along the way, and I didn't have to go into any detailed background about the historical figures that we discussed during the tour.

I was following a walking tour that Tess Johnston and others had devised for their book Six Walks in Shanghai. We meandered through more back alleys to Nanchang Road, which I like to call Revolutionary Road, since so many revolutionaries from the 1920s lived on or around this street.

Our next stop was the Joffre Terrace (淮海坊) another longtang complex that once housed literary and artistic giants of the early twentieth century such as Ba Jin and Xu Beihong, as well as Xu Guangping, the wife of the writer Lu Xun who spent 12 years living there after his death in 1936 compiling and editing his collected works.

As I always do, I asked them to stop in front of Ba Jin's home for a group photo. Next door is the home of Xu Guangping, and we spent some time talking about how she met and married China's most famous writer of the early 20th Century. This old man living across the alleyway had a few things to say about the apartment that Ba Jin had once occupied, namely that it was being rented out.

We then continued on our tour down Nanchang Road, and after a long walk we reached 100 Nanchang Road which housed the former editorial office of the New Youth literary magazine (新青年), run by Chen Duxiu, one of the co-founders of the Chinese Communist Party. It was there in the early 1920s that Chen published China's most influential literary journal. It was only a short walk from there to the schoolhouse where the fledgling CCP held their first meeting in 1921.

The walking tour ends with a stroll through the old French Park, built in 1909, which became the lodestone for one of the richest (culturally and financially) neighborhoods in Old Shanghai. Passing through the park, we stopped at the statue of Marx and Engels to pay homage to the founders of Communism, and then strolled through the rose garden, which we were delighted to find was abloom with roses of many colors. I told them about the nightclub that fronts the garden, now known as Muse at Park 97, and how influential it had been to the nightlife scene of the city in the early 2000s. We exited at Gaolan Lu and passed by the home of KMT general Zhang Xueliang, then stopped in front of the home of Sun Yat-sen to pay homage to the founder of Modern China.