Shanghai is no stranger to jazz, having been the jazz capital of Asia back in the 1920s and 1930s. Even at the height of WWII, much to the consternation of the resistance movement in China, Shanghai was still dancing up a storm in hundreds of jazz cabarets operating in the city. As Duke Ellington was fond of saying, jazz musicians then composed and played for dancing. Sometime in the 1950s, jazz became largely divorced from dancing and instead became an art form to be listened to and appreciated with great intensity, much as classical music had done in an earlier age. Meanwhile, rock and roll arose out of an amalgam of swing dance music and electric blues, and dancers shifted to that new musical trend. Then came disco, then hip hop, then house and electronica—you get the picture. All those decades, the soldiers of jazz carried on, developing their own styles and rhythms out of the art of improvisation and ensemble playing, while either cleaving to the old jazz standards or creating new ones.

Since 1980, when the Old Man Jazz Band was first formed at the Peace Hotel, Shanghai has revived its own identity as a city of jazz, while also becoming a city of blues, rock, hip hop and other musical styles. Yet none of these other styles has achieved the iconic status of jazz in this city. Little wonder that the most influential and well known live houses in the city have focused on jazz and its cousin, the blues. Then there is the JZ Club. Started in 2004 as a place run by musicians for musicians, this club quickly became the premier live jazz house in the city. The work of owner Ren Yuqing in running that club as well as the JZ School and JZ Festival makes him easily the most influential figure in the recent history of jazz in China.

For over twenty years, the House of Blues and Jazz and the Cotton Club, and later the JZ Club, have brought great jazz and blues artists into the city from abroad or else trained them here in Shanghai, as in the case of the Chinese conservatory musicians who have become some of our most exciting jazz artists. While the Cotton Club recently shut down, there is hope that it will open again soon. The House of Blues and Jazz still trucks along on Fuzhou Road near the Bund, and recently it has hired a blues band from the USA and Europe featuring bluesman Derrick Walker to liven up the Shanghai nights. JZ has moved to a new location in a sunken mall on Julu Road, surrounded by a cadre of craft beer bars and restaurants that attract a largely expat crowd, where it still attracts some of China’s top jazz talents and a crowd of status-seeking or jazz-loving big spenders.

Now there is a new kid on the block: Jazz at Lincoln Center. Managed and directed by Wynton Marsalis, who once made an appearance at Shanghai’s Cotton Club and HBJ several years ago, Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York with its marquee club Dizzy’s has franchised out to other cities including Shanghai. In addition to educating the public about jazz, this club aims to bring the city’s jazz scene to dizzy new heights, and already it has succeeded in doing so.

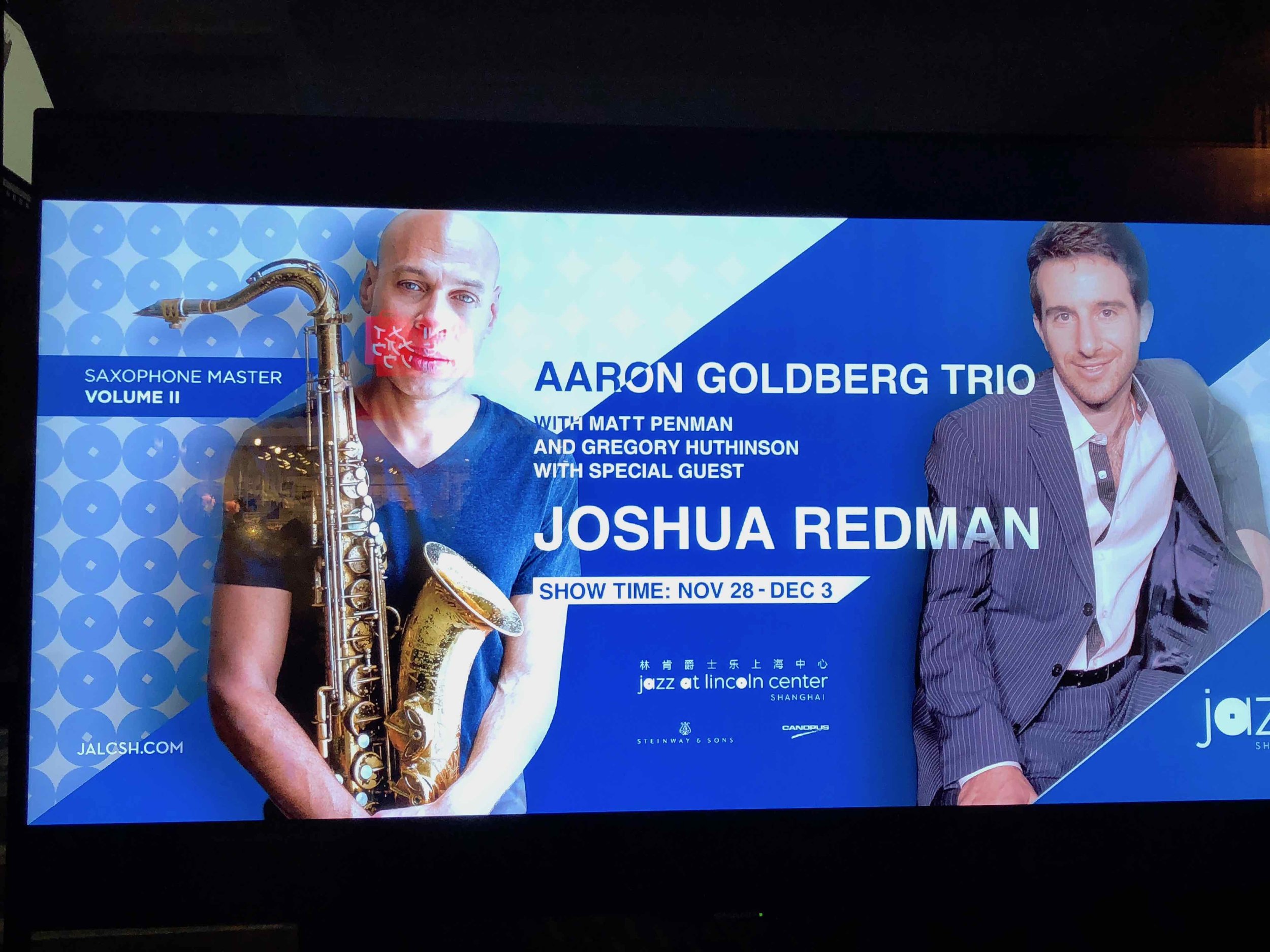

Last Friday, I attended a ‘soft opening’ show at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Shanghai club for the first time. The club has booked a jazz trio led by pianist Aaron Goldberg with Matt Penman on bass and Gregory Hutchinson on drums, and they were here for around three weeks. On Friday night, Dec 1, they were joined by one of contemporary jazz’s truly great saxophonists, Joshua Redman. I saw Joshua perform with pianist Brad Melhdau last year at the JZ Festival on the Shanghai Expo grounds. It was a memorable performance, with their music reverbating across the Huangpu River, and I was looking forward to seeing him again.

The club itself is posh and elegant. It is located a grand old colonial-era building on East Nanjing Road within spitting distance of the Bund and the famed Peace Hotel. That evening, the club was modestly filled up with a half-Chinese, half-expat or tourist crowd. Our own group of seasoned American expats (‘settlers’, really, is the term I prefer) and our Chinese wives took a table right near the stage. We ordered dinner and drinks as we waited for the band to start. They did so around 8 pm and played two fantastic sessions, with Joshua Redman joining in for both sessions.

Playing on a Steinway grand, his back to us, Aaron and the trio started out with two pieces by his ‘personal heroes,’ pianists McCoy Tyner and Ahmad Jamal. The latter song ‘Poinciana’ eased us gently into a samba rhythm as Aaron took the lead. Bass and drums took on a steady groove behind Aaron’s dexterous progressions up and down the keys. I could see Latin dancers in shiny outfits and swishing satin skirts shimmying right up to the stage. Too bad we are in a different era, where nobody dances to jazz anymore. Towards the end of the piece, Aaron took the back seat and Gregory’s drums took over the wheel. Under the spell of his Caribbean-influenced drum beats, you could imagine a multiethnic tribe of people dancing around a beach bonfire on a torrid island night.

Lest my imagination runs away with me, let us return to the night in question. Of course, there was no dancing. There hardly ever is in these clubs, since they are built to make money by selling real estate—i.e., tables for dining and drinking, which are usually set up all the way to the stage. There’s hardly room for dancing in these clubs, even if people were inclined to do so. The only exception is House of Blues and Jazz, which leaves a small space between stage and tables, and which always encourages a few brave and alcohol-fueled dancers to exhibit their skills in front of the crowd. In this club however, the message behind the layout and ambience was clear: Sit down and listen. To be sure, not everyone was listening. A gaggle of giggly gals were gabbing away at a table next to us throughout the performance as they exchanged photos on their mobile phones. But I have to say that most people I saw there that night were paying due respect to the jazz masters on stage. Certainly, we were, and our table led the whoop brigade, making sure to loudly and firmly declare our appreciation and admiration for the band after each song.

After the warmup by Aaron’s trio, we cheered and hollered as Joshua Redman joined the band, forming a quartet. As Joshua started up, a cameraman with a tripod started snapping photos, getting up close to the stage in Joshua’s face and standing in everyone’s way. Interupting a hearty solo, Joshua told the guy in no uncertain terms to buzz off, and he did.

Joshua now fronted the band, sharing leads with Aaron. He took center stage and was a commanding presence, a force really, as he crafted his solos with great precision and lung power. After each solo, his MO was to step to the side of the stage and sit there on the edge, letting Aaron or the other band members take over the crowd’s attention.

It was a groovy night, with all four band members pouring their heart and souls into their music despite a less than stellar crowd. Joshua seemed to have stepped onto Earth from another planet entirely. He came across as a celestial figure, one of Bowie’s proverbial starmen. His horn was like a part of his body, and he would go on long, extended solos with some sort of circular breathing skill that was amazing to watch as well as listen to. As the solos mounted, they took us on a journey somewhere out beyond the solar system--and no, other than alcohol I wasn’t on anything but the rush of music. Sometimes, while performing a funky solo with a lot of beats and bleats, his hips would move back and forth as if he were making love to the music. That’s the best way I can put it at least.

By contrast, Aaron’s playing was cool and cerebral. His solos were performed with great dexterity and keen intellect, deeply rooted in jazz and blues traditions. There was a lot of fancy footwork—or handwork to be precise—in his movements up and down the keys as he soloed in fluttery flights, while otherwise his accompaniment was rhythmic and subtle as he let the others take their turns. Matt Penman played a sultry, sinuous, winding bass progression on some of his own solos, and Gregory turned up the volume on drums, usually towards the end of a more upbeat song. But mostly it was Joshua taking center stage and taking us along with him into another dimension of time and space, much as Coltrane had for his audiences.

The play list included jazz standards like ‘Remember’ by 1920s songwriter Irving Berlin, which took us back to Nightime in Dear Old Shanghai and the era of the foxtrot. The ghosts of Whitey Smith and Serge Ermoll, two jazz bandleaders from that era who used to play at the nearby Astor House and Peace Hotel, appeared in the room momentarily, admiring Joshua’s skills and wondering how they could hire this guy for their bands. Yet this song was grounded in swing, a rhythm that those white American and Russian jazz bands hadn’t quite achieved, and which Shanghai did not truly experience firsthand until Teddy Weatherford came to town in 1926 along with Jack Carter and Valaida Snow and played at the nearby Plaza Hotel. But it was Buck Clayton in 1934 who brought it home with his Harlem Gentleman playing at Shanghai’s Canidrome Ballroom in the heart of the French Concession. Buck and Joshua would have gotten along just fine.

Next it was on to Chick Corea’s masterpiece, ‘Rainbows’, and then back to an old standard from the 1940s, ‘We’ll be Together Again,’ followed by ‘Tokyo Dream’. After that series of ups and downs, groovy blues-based jazz and cool Latin rhythms, Aaron announced that they were going to play an original composition of his that he wrote for Joshua years before, called ‘Shed.’ This piece has Aaron playing out a 5-4 groove that moves from the key of F min to C sharp min, then modulating up to other keys and progressions. It has a very noir flavor to it, as if we were watching a spy thriller or a murder mystery unfolding on a cold metropolitan night. In other words, this song feels like it could be made for a film. Joshua performed a solo that sounded like at times the pattering of rain over the city, other times like a terrified victim being chased down by a cold-blooded killer, screaming as she runs through the dark alleyway as the drama plays itself out.

This was followed by a groovy, bluesy, poppy, floppy, funky, clunky, chunky piece that started out by showcasing Joshua’s prodigious skills as a one-man band. Upon the band’s entry after his solo effort, I started clapping my hands to the downbeat. In another place and time, this piece would have got the whole crowd up on their feet clapping and dancing and jiving to the funky beat. But no, it just wasn’t that sort of crowd, nor that sort of place, so everybody just sat, listened, and enjoyed. At the culmination of the piece, Joshua and Aaron traded fluttery solos, riffing off each other, then joined together in a glorious harmonic duo. Matt was then given the chance to strut his stuff on bass, plucking out a cool solo that walked us around town in a Zoot suit twirling a huge pocket watch.

The first set lasted about 45 minutes. The second set was about the same length. Again, they interspersed some slow, contemplative pieces with faster, more energetic ones. They began with a song by Robert Hutcherson called ‘When You are Near.’ Aaron’s skills and sensitivity as a balladeer came through in this song, and Matt Penman also had an opportunity to join in with some solo work of his own.

Joshua then returned to the stage and led a more down-to-earth version of the song ‘You’re My Everything’, which gave Aaron the opportunity to show off his jazz chops as he cascaded back and forth across the ivories, and finally they traded off on some ethereal riffs. This was followed by a more bluesy, swirling, mesmeric piece with an oriental flavor in the key of Asia Minor, where once again Joshua and Aaron riffed off each other effortlessly as if they’d been playing together for many years (which I suppose they have). Towards the middle, Joshua took flight with his solo, which arched around a series of jaunty, jumpy, jingly, jangly riffs that Aaron later echoed in his own solo. Once again we were climbing to the stratosphere and beyond.

They were then on to Joshua’s own song, ‘Come What May’, a slow, languid, late-night ballad, with Joshua conjuring up an aching, regretful tone on his sax, and Matt on bass joining in the mood. The unexpected resolution into a major at the end brought on goosebumps. They sped up again with a poppy, beboppy piece by Joe Henderson, ‘Tetragon’ punctuated with Joshua’s occasional shouts and calls and also his most energetic solo of the night. The next tune was also a Joshua Redman composition called ‘I’ll Go Mine,’ which he announced with a long drawn out solo, sans accompaniment, that climbed into the highest registers of his instrument and back down again for some low-pitched pops and blows, once again showing his skills as a one-man band.

During the break and after the show, we chatted with the band members, although Joshua opted to return to the dressing room. Gregory and Aaron spent some time talking at the bar to the members of our group. At the very end, Joshua popped his head out and engaged us in a brief conversation. Naturally, I quizzed them on the history of jazz in Shanghai. Of course they were familiar with the name Buck Clayton, though they were surprised to learn he played here in 1934. On the other hand, I was surprised they hadn’t heard of Teddy Weatherford. Then again, outside of the small circle of Old Shanghai jazz aficionados (not to mention historians of jazz in India like my friend Naresh Fernandes) who has?