Right now, the entire world is watching the unfolding of this dramatic global outbreak of Coronavirus aka COVID-19 with great trepidation and fascination as we ponder the impact and significance of the Coronavirus for China and the rest of the world. As a historian of China and of Shanghai in particular, as well as a long-term China resident (one might even use the word “immigrant” though I prefer “settler”) my own reaction to commentaries about the rise of the virus, its causes and consequences, and the extreme steps taken by the government and people of China to counter its spread has been one of caution. When discussions arise on Facebook, LinkedIn, or other social media, where like so many others I am reading an endless parade of news articles and commentaries that friends and colleagues post daily, I often invoke the Chinese phrase yan zhi guo zao 言之过早 “it’s too early to tell.”

Playing the Blame Game: Chinese Government and People’s Responses to the Initial Outbreak in China

Some of these articles and commentaries focus on China’s slow initial reactions to the viral outbreak and the presumably intentional suppression of news of the outbreak by the government of Wuhan and implicitly the central government in Beijing, as the case of poor Dr. Li suggests. These are of course disturbing reports and they must be taken seriously. On the other hand, how much do we really know at this point about internal discussions and motivations of China’s local, regional, and national government, which are normally quite opaque to begin with? We must assume that the desire to prevent widespread unnecessary panic must have been at least a partial motivation.

As for the question of local and regional officials underreporting or falsely reporting to the national center, this is an age-old problem in China and elsewhere, and especially in top-down hierarchical structures of governance and authority. Such a historical perspective does not reconcile the issue, but I do think we need to be more cautious about pinning the blame for the outbreak on Chinese officials at this point, or claiming this to be a “China problem” or an issue of a “totalitarian regime” (which China is not, in my own humble opinion.) Hopefully in future as more data comes forth we can provide more sophisticated and nuanced analyses of what transpired in the early phases of this outbreak.

Other news reports and commentaries focus on China’s decision—both a top-down and bottom-up decision as I understand it and as I lived it while still in China last month—to quarantine people, cities, and communities, in order to prevent the spread of the virus throughout Chinese society, and also abroad one assumes, although that may not be the primary intention. Again, I believe we must wait and see to assess how well these have functioned to mitigate the impact of the virus. It is still too early to tell, and we don’t know yet what the inevitable relaxation of these controls will mean for a country that is now so deeply connected now to the rest of the world. These are issues that historians, social scientists, and health experts will be mulling over and arguing about for years to come.

In my previous blog post, which offers some suggestions to Americans and others around the world about what to do and what not to do in the face of the global pandemic, I wrote “Don’t blame China.” My point is not that China is blameless. Rather, the opinion I am offering here is that pointing the finger right now doesn’t really help us to determine the causes and consequences of this event nor to manage this unfolding crisis in an effective way. There will be plenty of time in the future, when we have a much more comprehensive, nuanced and well-rounded perspective on the current crisis, to point fingers and assess blame, as well as judging the consequences and effectiveness of various policies and campaigns to prevent the rapid spread of the virus.

Is China All Wet? Transformations of Wet Markets in Urban China Since the 1990s

To be sure, China must indeed take responsibility for some factors that contributed to the rise and spread of this virus. If one accepts the most obvious and reasonable proposition that the virus was caused by the close proximity of a variety of animals in a local wet market in Wuhan, then the Chinese government should indeed take responsibility for this situation and take serious measures to control these wet markets and prevent the sale of wild animals in particular. Even domestic animals such as pigs and chickens lead to outbreaks when sanitary conditions surrounding such markets are not carefully controlled as has been demonstrated repeatedly in the past. On the other hand, is it really possible to do so in such a vast country and one that depends so much on these markets, whose traditions go back centuries if not millennia, to feed a population of 1.4 billion people?

I have lived in China, mostly in Shanghai, and more recently in the nearby city of Kunshan, for at least fifteen of the past 25 years. When the subject of wet markets comes up, as a historian and long-term resident of China (I first visited in 1988 and started living there in 1996), I can vouch firsthand that these markets have indeed been subject to increasing local controls over the past few decades.

When I first travelled in China as a college student in the late 1980s, every town and city I visited had ample wet markets, where fish, poultry, and other farm animals were sharing space with other animals, some of which seemed more destined for zoos than dinner tables. I recall in particular visiting a wet market in Guangzhou and seeing all sorts of wild creatures from owls to furry mammals that belonged in forests and other natural environments, and not in dirty cages.

In Shanghai, while such exotic creatures were far more rare, wet markets of all sorts nevertheless abounded in the city in the 1990s when I first lived there. Nearly every neighborhood in the city had a street that was dedicated to a local wet market selling live fresh seafood as well as other live animals such as chickens—not pigs, sheep, or cows though—they are slaughtered elsewhere and their meat, flesh and bones are brought to the market and sold there.

These live wet markets were naturally quite messy, with plenty of water sloshing out of buckets containing the live aquatic creatures and from hoses splashing on the streets, and remnants of produce, cut-up animals, guts and such covering the streets, and they were frequented by a constant parade of buyers and sellers (is it any wonder that Shanghainese people take off their shoes when they arrive home?). How ironic then that during those times, we did not witness any major breakouts of deadly viruses, at least not that I can recall.

Around 1999, perhaps as part of the buildup to the Global Economic Forum that Shanghai held in 2001, Shanghai began to systematically shut down these outdoor street wet markets, clearing up the streets for other forms of commerce. At the same time, they built warehouse spaces to host these wet markets. By the 2000s, nearly every neighborhood in the city had a semi-open wet market housed in a corrugated-roofed open warehouse, and that is pretty much how things continued until this year. This transformation of wet markets from streets to warehouses both eased the traffic flows of an already congested city at a time when more and more cars were flooding the roads, and also helped to create more sanitary and manageable conditions for the wet markets.

To be sure, these semi-indoor wet markets were still rather unsanitary by some standards, but they were far more sanitary than the outdoor street markets, and better controlled overall. This I understand is the kind of wet market that is the reputed source of the virus in Wuhan. So it is funny that these are the sorts of markets that ultimately led to this breakout, and perhaps others as well.

Perhaps the street markets were not so unsanitary as one assumed? And perhaps the warehousing of these markets actually created the conditions for far more deadly viruses to arise and transfer to human beings. The warehouses forced everyone into even closer proximity, they were not aired in the way outdoor street markets were, and they also provided spaces for sellers to hide creatures that may not be sold legally on the open street markets. This is just a speculation, but it bears out with the Wuhan case.

Ch-ch-changes! China in the 1980s-90s and Now

Another difference is that back then, certainly in the 1980s and less so in the 1990s, Chinese people didn’t eat nearly as much meat or fish as they do today. Consumption has changed dramatically in China since those days. And people were generally healthier since they used their feet and bicycles to get around a lot more than they do today.

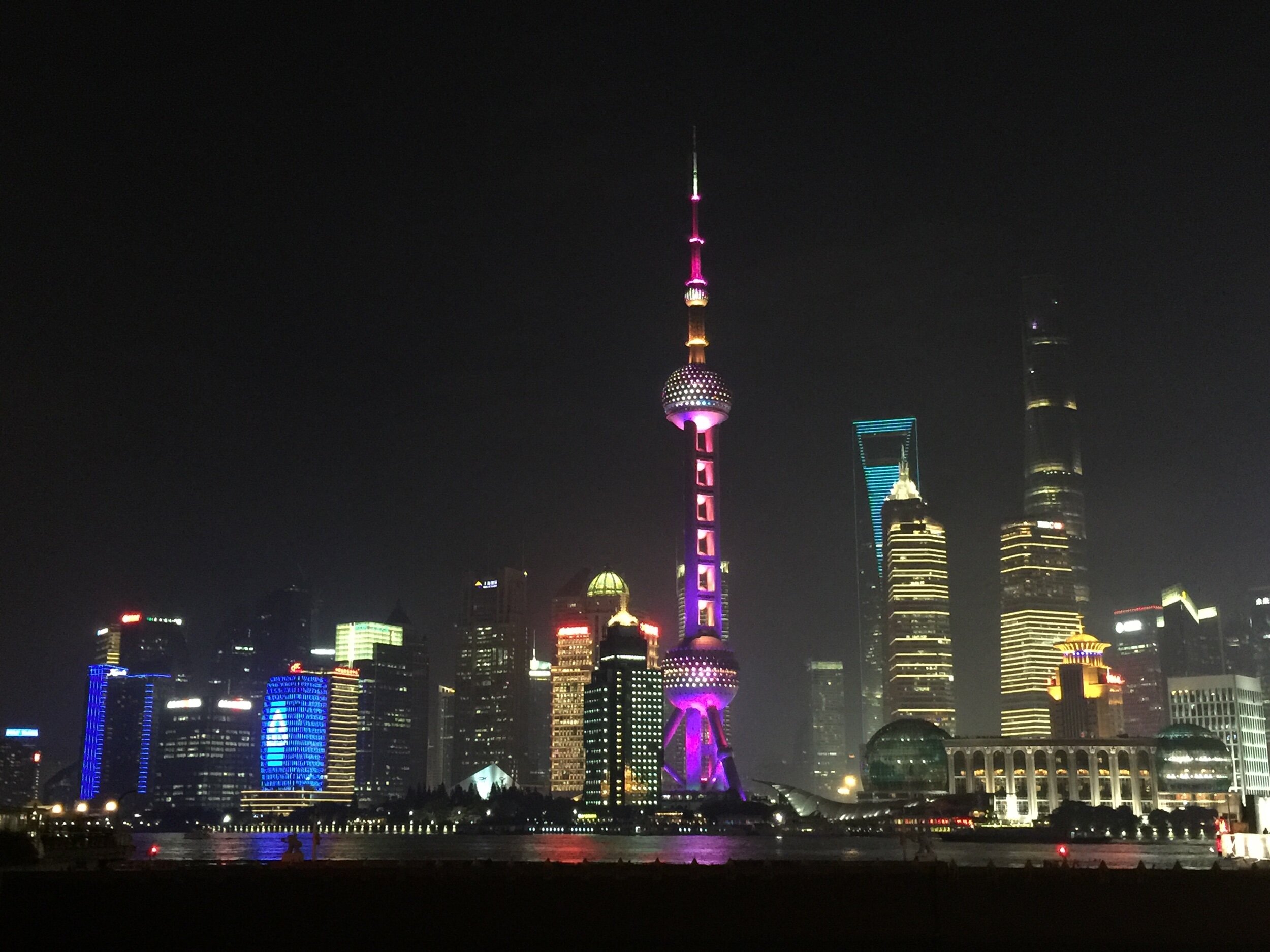

There are many other differences between now (2020) and then (1990s) as well. For one thing, China’s cities are now far more populated than before, and they are home (or temporary residence) to millions of people from other parts of China and beyond, and to a much larger flow of people and resources in and out of the city. In the 1990s, Shanghai’s population for example was still relatively homogenous, because of the strict hukou 户口 system and the prevention of migration into cities during and after the Mao years. The great majority of Shanghainese were people whose families had migrated to the city from nearby towns and cities in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Anhui and many other provinces during the Republican Era (1912-1949).

Things started to really open up in Shanghai and other cities in China by the late 1990s and especially since the 2000s. Today, Shanghainese people often will blame the government for “polluting” the city with millions of migrants from other parts of China, whom the Shanghainese dismissively call waidiren 外地人,literally “outsiders,” but with a pejorative connotation.

Some would even say that there is a “racist” element to these social distinctions, with the waidiren serving as the “Other,” in the parlance of academia. I’ve often heard Shanghainese people say that back in the 1980s, the city was far cleaner and more well-managed than it is today. There is a certain nostalgia about the city before it was “polluted” by millions of waidiren. One assumes that similar dynamics prevail in other large cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Chongqing, and yes, Wuhan.

Obviously, it is China’s deep connectedness with the world that is the key difference between those times and now. In the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese people travelled relatively little, whether within their own country, or elsewhere in the world. The economy was much much smaller than it is now. Certainly the amount of tourism both inside and outside of China was far far less than it is now. Today, millions of Chinese tourists, students, and businesspeople travel widely and live abroad, thus exacerbating global fears about China’s influence on the world. At the same time, these people are bringing the country’s massive brain power, manufacturing capabilities, and capital to the rest of the world, and increasing the reliance of universities, hotels, airlines, and myriad other businesses on the people of China.

Now that the so-called Coronavirus or COVID-19 has been unleashed around the world, it has ceased to be a “Wuhan” or “Chinese” virus and has instead become a global medical crisis. Yet the tendency to “blame China” for the outbreak is still there. I suggest that we hold off on pointing fingers. Let’s concentrate instead on being safe and sane and doing our best to prevent the further spread of this unfortunate viral transmission from animals to humans, which is more closely related to the human condition and our relationship to the world of nature than the political and cultural dynamics of any particular country, region, or people.