After Riley was re-arrested in 1941, he was brought again to court where he and his counsel H. D. Rodger made a plea for leniency. This article recounts that plea along with some interesting (if dodgy) info about his own personal and family background. Will we ever know the whole truth about Jack Riley? I doubt it...

SHANGHAI LAW REPORTS: U.S. Court for China Gaming Charges U.S. V. “JACK” E. T. RILEY

(North China Herald Apr 9, 1941 p. 66)

COUNSEL: Mr. Leighton Shields, District Attorney prosecuted and Mr. H. D. Rodger for defendant. Before Judge Milton J. Helmick (Sentenced to 18 months imprisonment)

Shanghai, Apr. 1.

After an unsuccessful verbal battle by his counsel. Mr. H. D. Rodger, and a prolonged statement in which he asked to serve his time in the local gaol, “Jack” E. T. Riley, slot machine operator and big-time gambler, was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment in McNeill's Island Penitentiary by Judge Milton J. Keimick in the U.S. Court for China yesterday.

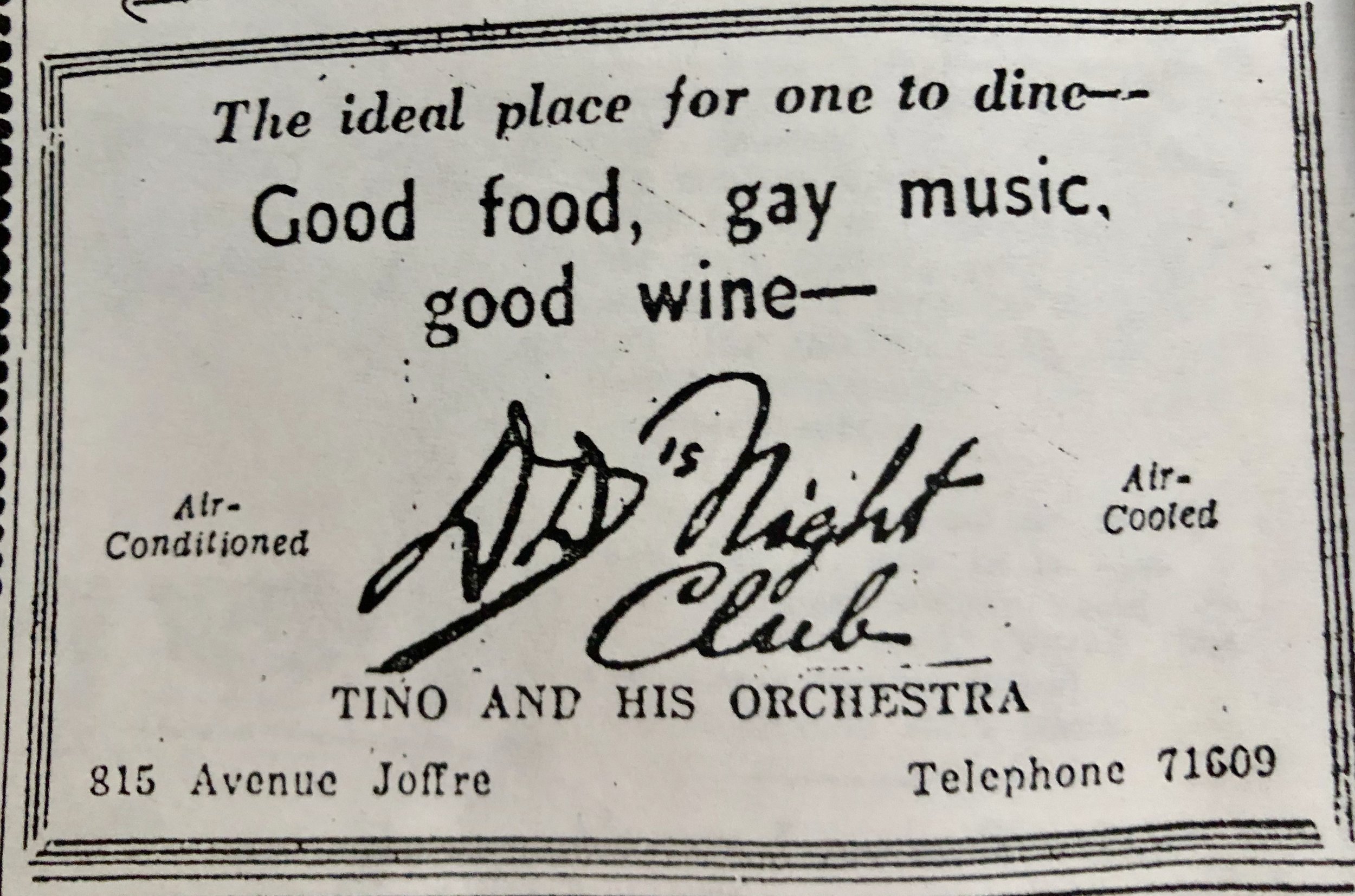

He was convicted on numerous counts of engaging in commercialized gambling here, operating a crap table at Farren’s Night Club and slot machines at D.D’s and various other establishments. In a tirade against a certain section of the press here who had called him a “gaol-breaker,” and “fair-weather friends" who had “kicked him when he was in trouble,” he declared that a Mr. Chisholm had given him a “Rush Act” 18 months ago for $100, for which he said he still held an I.O.U. He was given 18 months on the first three counts and one month on each of the other counts, the sentence to run concurrently.

“I have been painted by the former prosecuting attorney and the press as a very hardened criminal,” Riley declared, and went on to say that they had associated him with machine guns and gaol-breaking and that, people here were entirely ignorant of his life except the worst side of it. He described his act in jumping his U.S.$25,000 bail as a foolish act. On the advice of his counsel he had pleaded guilty to the gambling charges.

Referring to the report that he had escaped from prison in Oklahoma after serving two of a 25 year sentence for conjoint robbery, he asserted that he was convicted purely on circumstantial evidence. Later on he described how he became an unwitting tool in the hands of the actual participants in the robbery who had engaged him to drive a car to the scene of the crime and who escaped while he alone was arrested.

Reverting to the question of his American citizenship, he told the court that he went to the American Consulate in 1932 to swear an affidavit that he was an American, as he was desirous of returning to America to clear up the Oklahoma affair but the authorities would not permit him to go. He admitted that he was unable to give them his right name. He had even gone the length of making preparations to have a retrial of his case in Oklahoma.

Talking of slot machines, Riley said he had received them in parts through the Customs and Post Office by parcel post and thought his national status was similar to those of White Russians here who are under Chinese jurisdiction, as he had not been registered and the American authorities here would not let him register in 1937.

“About my running away here, I am not sorry,” he added, and disclosed that he had an insurance policy which would take care of him financially for the rest of his life. He would not have to go to the poor house. He was not sorry about the U.S.$25,000 bail which he had for-feited, characterizing, it as a gamble in which he had lost. Speaking of an insurance man who had given evidence against him on a former appearance, he declared with acrimony that the man had solicited a policy from him for which he had paid for twenty years, in advance. He was at a loss to understand why the parly concerned should testify against him.

“Everyone knows that I was in the U.S. Navy," he continued, and declared that he had been commended for bravery and had been discharged as a second class officer, not as a seaman as had been alleged against him.

Dwelling on an affidavit which Mr. Chas. Richardson, Jr. and the Marshal of the Court had mentioned was made by his mother to the American authorities that he was adopted into a “Riley” family, accused asserted that his mother did not know a thing about him since he was four years old. His father, he said, had placed him in an orphanage before going to the gold-fields, when he was at the age of four, and died when he (Riley) was eight years old. He declared that he had never been adopted by anyone and had sold newspapers in America and worked his way through school.

He went on to say that he had adopted the name of a crony, E. T. Riley, before coming out to China from San Francisco. After remarking bitterly: “This just shows how much my mother knows about my life, since she left me," he referred to a Mr. Maloney whose name also had been brought out and said that Maloney was an old pal whom he had helped, When he had amassed a fortune, he declared, a lot of relatives had written to him.

“I envisioned spending the rest of my life in jail and didn’t have the will power to come back,” Riley continued, adding that if his bond had been revoked or he had been put simply on his honour to return, he would have not jumped ball.

After expressing his regrets for running away, he disclosed that during his freedom he had visited the French Concession in the evenings and asserted that not a single policeman would arrest him, declaring that they liked him and observing wryly, ‘‘That is how much cooperation the Marshal got from the French police."

Riley went on to say that he had ample opportunity to leave Shanghai, but did not have the heart to go to a country which was not the ally of America, preferring to remain here and to take “the rap.” It had been suggested by the prosecution that he was a criminal even before the charge was brought against him in Oklahoma, and declared that he had not seen the inside of a jail before he was 26, although he had no parents to look after him. His grandfather was a well-to-do cattle man, Riley continued, but had allowed his six children too many privileges and his father had died from drink.

All his life he had abstained from drink and smoking, Riley went on to say, adding that he liked cards, cinemas and dancing and had his bad habits, observing that he was no angel. He had joined the navy at Salt Lake City at 19 and later became associated with the merchant marine after a perfect record of four years.

After coming here, he said, he had worked for three years with the Shanghai Power Company, which job he secured through Mr. Fessenden. Being fond of craps he had played dice at night, winning more in one evening than his whole month’s salary. He said he had worked eight years for Gande, Price and they had trusted him with “everything they got.” After declaring that his commercial record here was above reproach, Riley said he had never owed anyone and even after he had jumped bail his lawyer had received $3,000 legal fees. He had received many notes and bad cheques.

“It is not my habit to put money over my honour and name,” he declared, and said that he had given alms to old people and had a wide circle of friends; all of whom were poor Chinese, Russians and Eurasians and would not be afraid of putting his case before a public vote. He had not attended cocktail parties and his idea of settling down was to be a cattle ranger. He admitted a failing for shooting craps, which he said had resulted in his being kicked out of the Navy twice.

Did Farren’s close up after his arrest? Riley next asked, and pointed out that the day slot machines were taken out of the Marines Club, the price of drinks had gone up 30 per cent, and they had made 35 per cent, of the profits of the slot machines, which prompted Judge Helmick to observe “Yes, but you got the remainder." Riley explained that he had to pay for the upkeep of the machines which had been brought out from Chicago. He was paying income tax to the Chinese authorities and all these years had not been told by anyone that he had no right to operate slot machines here.

After saying that he had not got a “break,” Riley accused the Marshal of the court of getting evidence against him behind his back. He had bought an interest in the building housing the Farren’s resort, he said, to help a friend who was going to lose his whole business. He denied being a “big shot” at Farren’s pointing out that if that was the case he would not have operated the crap table, but would go where the “big money” was.

Continuing, he said he had never been inimical towards the press, but they had kicked him when he was in trouble. They had accused him of having machine guns which he emphatically denied, declaring that he had never asked a permit to carry a gun in his life.

“Somebody has got to be the goat for the gambling in the badlands and I am the one”, he went on to declare, and pointed out that poker and other games were being played at the American Club and others who had been warned to lay off, which warning had not been given to him.

The gambler should be as guilty as the operator of the gambling house, Riley said and asked that he be allowed to serve time in Shanghai, in which case, he said, he would pay his own passage later to America.

In opening the case Mr. Leighton Shields, the District Attorney, submitted numerous documents to establish that Riley was a native-born American citizen, and announced that the proceedings would be a continuation from where they had left off before Riley made his sensational disappearance which resulted in the forfeiture of his bail. He understood that accused was desirous of reiterating his former plea of guilty of the offences mentioned in the information filed against him. The court would deal with the question of sentence after hearing the accused.

Mr. Shields then referred to the 17 counts brought against Riley under the District of Columbia Code, and said that there were a number of counts which were parallel, being alternatives of one another, and suggested that with a plea of guilty the court had the discretionary power of making the sentence run concurrently., It was incumbent upon the American authorities, he said, to see that their citizens behaved themselves and when their conduct became a nuisance it would be time to have it stopped. The offences charged against the accused were considered to be against public policy which was a very “indefinite classification.”

Counsel said he was advised that slot machines were permitted to be operated in the French Concession if licensed and certain Americans were reported to be similar offenders and would be subject to prosecution and conviction the same as Riley. He was aware that the machines were operated on American ships like the President Lines. If the thing did not amount to a public nuisance, counsel submitted, the court could overlook the gravity of the charge, which was a technical one.

Regarding the operating of gambling at Farren’s Mr. Shields continued, that was a far different matter as there was in it a distinct nuisance value. Counsel then referred to the raid made at Farren’s by unruly elements and thugs, resulting in people being killed, being exemplary of what the nuisance referred Lo would result in.

Riley had given the judicial authorities a whole lot of trouble, Mr. Shields added, and had placed certain officials even perhaps in physical danger in following him, and the court could not look upon his plea as an ordinary plea of guilt and must take a serious view of the case. Counsel went on to refer to horse-racing as a well-established institution here which was giving a lot of people harmless pleasure.

Mr. Rodger admitted in his address that Riley had operated a crap table at Farren's and slot machines here. Riley had bought the property on which Farren’s stood, he said, from the Chinese Overseas Bank; he was owner of half of the property and the lease to the present occupants ran out on January 1, 1941. It had not been suggested that Riley was concerned in the operation of the roulette tables at Farren’s counsel continued, and disclosed that a syndicate was in occupation. The property was purchased by Farren’s and Riley, he said, on April 9 1940. Later, he said, Riley sold his interest in the property to Farren’s.

Every American here, counsel pointed, was a member of the Race Club or a frequenter at the races and was liable to be prosecuted under the Code. “This law is antiquated law and has not been changed since 1929,” Mr. Rodger declared. They had horse racing today practically in all the States and people were getting lots of fun out of it. Apart from a couple of infractions of the traffic bye-laws, Mr. Rodger said, Riley had a clean record during his long stay here and stressed the generosity of Riley who, he said, had never turned a deaf ear to the pleadings of people who asked him for a meal.

During Prohibition, counsel pointed out, Americans here were allowed to indulge in liquor and could own bars and sell drink. As far as he knew a number of legislators themselves were attending the race tracks in Washington and he would ask for a minimum punishment, considering that the French Municipal Council was issuing licences for slot machines. Riley, he declared, had been sufficiently punished through the loss of his bail of U.S. $25,000, representing his life’s savings which had gone. The interests of justice would be served, he suggested, if Riley was sent to prison here for six months. Counsel then dwelled at some length on the case of Garcia and other cases of foreigners convicted here of operating gambling houses.

Mr. Shields in a brief reply stressed that it had not been the practice here to prosecute people who played innocent games and frequenters of race tracks. Operations of commercialized gambling was different, he said. It had been brought out that Riley had amassed a fortune, showing that he had conducted a very profitable business here. Mr. Rodger had not been to America for some time, he said and was not aware of condition there. Counsel doubted if legislators today could even find the time to attend the race tracks, as Mr. Rodger had said.