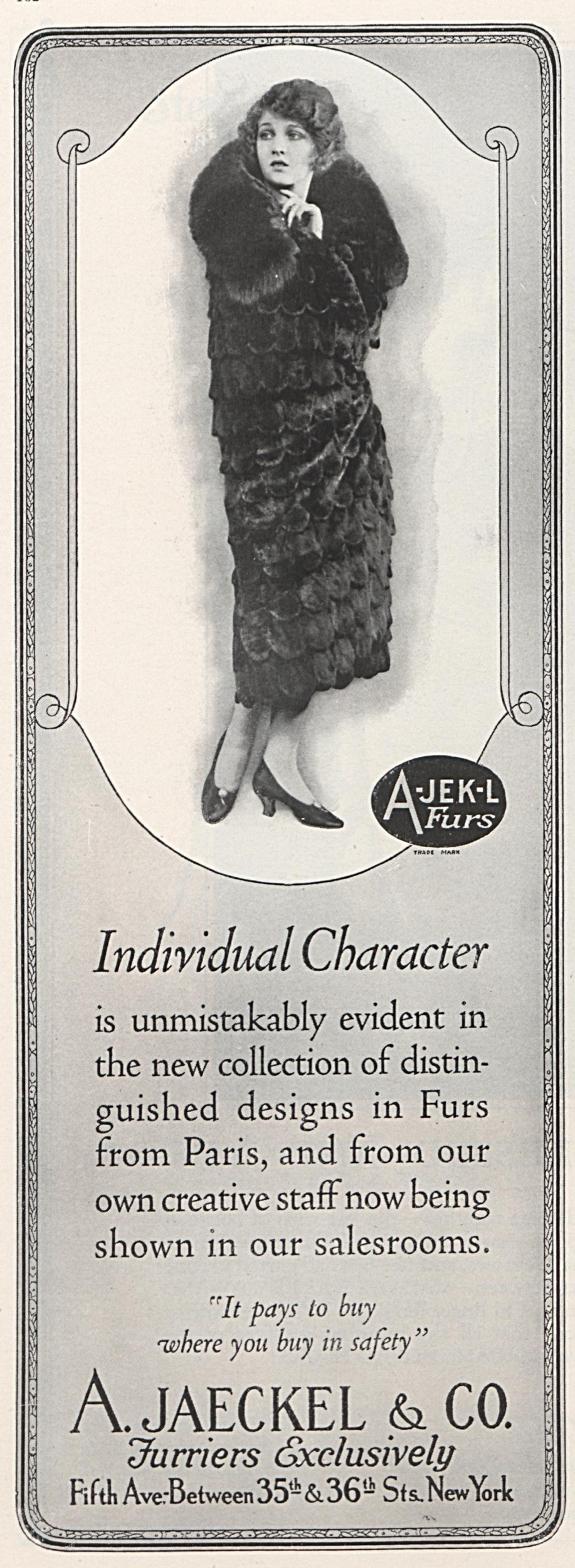

While searching old Shanghai newspapers for more evidence of the early phases of jazz and dancing in the city (a subject I never seem to tire of researching), I came across this article published in the USA’s Vogue Magazine in 1924. It is a fascinating account of foreign life in Shanghai with many interesting insights into the colonial culture of the treaty port era. The way the article describes Chinese as “background” to the colorful foreigners is very telling. Also, the article claims that Chinese society is a “caste” society which is quite interesting if not entirely accurate (certainly China did not have the caste system of India). What I found most fascinating of all was the detailed explanation of Chinese household servants and their various roles. One comes across many references to household servants in foreigners’ accounts of life in Shanghai during this era, but rarely with such detail. The article provides some keen insights into the amazing leisure life of foreigners that such servitude enabled. Finally, the section about Shanghai’s nightlife as a form of “slumming” dovetails well with the research I’ve done in the past and with the book I co-wrote with James Farrer, Shanghai Nightscapes. If I’d found this article before we published that book, the passage at the end of this article would surely have made its way into our book. The ads I’ve included here originally appeared along with the article in Vogue.

Social Life in Shanghai

Vogue Magazine, 1924

By Franklin Carl

AFTER three hours of golf or tennis on a steaming hot summer afternoon in Shanghai, one is as parched and dry as a bone, and so, at sunset, after a shower and a change, one drops into the American club for a series of cool drinks and a chance meeting with friends while looking down into Nanking Road, Shanghai’s gay white way.

The parade is a mosaic. It is mostly Chinese, and a huge part is of Chinese pedestrians, for out of the million and a half of Shanghai’s population, not one in forty is a white European or American. One accepts all the Chinese, dun coloured and inert, without personality, as a background for the white “foreigners” who are the high spots of colour in the parade dominating the street crowd, just as the small foreign population dominates and colours the life of the city.

“FOREIGN WOMEN” AND THE MODE

In the carriages and motors passing are French, British, Russian, American, and a dozen other types of women. Their style, despite the cosmopolitan contact, remains as clearly their own as if they were at home in their respective countries. The Frenchwomen are as chic and distinctive, the American women as individual and dashing, the British as sports-like and mannishly tailored, as in their native surroundings, and, nowadays, there is also the cream of the Russian refugees. It is a fashionable procession that is passing, but it has one feature that is striking. It is not le dernier cri for any woman of any country. Every one is just a shade, and just the same shade, behind the fashions of Paris, London, and New York, respectively. Every one is out of style, but all are out of style together and to the same degree, so that the effect is as smart and satisfying as if there were no later word in dress. It has an interesting corollary. If a newcomer is so unwise or unkind as to put on the latest thing in gowns, which she has certainly brought with her in her forty-odd steamer trunks, she immediately becomes unpopular.

One always brings letters, and a husband’s business connections are also social connections, so the process of becoming acquainted is rapid, especially in such a high-speed life as that of Shanghai, where every one is more or less a transient resident and each depends on the others of her own kind for spice and variety to life in a community out of touch with home.

Shanghai social life is a cluster of glittering, dashing bodies of foreigners with a nimbus of servants. The Chinese themselves, in daily touch with the foreigners, are, nevertheless, continents away in thought, sentiments, and customs. To the Chinese, we are magnificent barbarians. They copies our luxuries and conveniences, but they scorn our philosophies and our habits. However, both Europeans and Americans love China, because it is so flattering to the Anglo-Saxon sense of racial superiority. Democracy becomes a memory of another clime, while the present is a continuing experience of real supremacy. The poorest junior can afford at least one personal servant, and moderate wealth commands an establishment.

China has a rigid caste system which is based on command of wealth, as well as on birth. It ranges up from coolie labour of all kinds, through sub-divisions of service and business, to the pampered pets of fortune who hold a fat purse. The average American fits very high in that scale by income, and, whatever his personal attributes, is from the moment of his arrival a member of an exotic aristocracy.

THE SERVANT PROBLEM IN CHINA

In the Chinese castes of labour the divisions are inflexible. A coolie may become a house boy by good fortune, but a house boy will starve before he steps down to become a coolie. No one grade of labour will do the “pidgin” of another grade. For example, the most modest household requires five servants. The “boy” is majordomo, and looks after the service of the table, the stores, the wine-cellar, and the other servants. The cook is an artist, the lord of the kitchen range. By the Chinese, he is rated as the social equal of a doctor, and he will do nothing menial. All such work is assigned to the second cook, or “learn pidgin.” The coolie scrubs floors. The amah is lady’s maid. Not one of these would do a stiver of the work of the others. He would rather lose his place than to lose his “face.” Indeed, the Chinese staff is not unlike the domestic staff of many an English household.

Any household more complex than the “most modest” one has correspondingly more servants. The result is the essence of luxury. Service extends to the last detail. One has a separate groom for each separate one of a string of ponies. One must, because one groom will not take care of two ponies. At golf, one has a caddy to carry the bag and one or two fore caddies who follow the ball. These are friendly little creatures, too. When they mark the position with a little red flag, if you are at all noted for generosity, they will improve the lie of the ball, or you will find you did not drop in the sand-trap, as you thought, but cleared the bunker.

SPORTS MADE EASY

A flock of coolies drags the houseboat along the inland canals all through the week-end party, and the guests, as perfectly attended by the servants as at home in Shanghai, have nothing to do but rest, which they do so strenuously as to arrive at home, Sunday night, tired out. A crowd of coolies carries the racing shells down to the water when the club crews go for rows during training for the international regatta at Henli, and wipe and groom the boats into perfect condition after each spin. There is no work or pleasure that service does not touch. One does not even stoop to pick up the balls at tennis. Small boys retrieve them.

In Shanghai, there are many household staffs of fifty and seventy-five servants. Service is subdivided, each servant having his restricted duty, which he never exceeds. This is carried to the point of absurdity, as in the case of the “goldfish coolie” in one establishment, whose sole duty it is to “bathe” and feed the goldfishes. The whole background of life in China is made up of flawless Chinese servants. In America, we have nothing which more than remotely resembles this perfection of service. And these marvellous servants are on duty for twenty-four hours a day. they almost never leave, and, when they do, they provide a substitute as a matter of course.

As it grows nearer eight and the street darkens after the long summer twilight, one leaves the comfortable observation posts at the club windows to hurry home to dress. “Boy,” one calls, and the nearest white-gowned attendant hurries forward from the cloud of “boys” standing at attention against the wall. “Boy. go catch the car chop-chop.” One does not expect literal obedience, because the boy is not a messenger. That is not his “pidgin.” The boy calls to the door coolie, the coolie to the doorman, the doorman to the chauffeur, and down below the club windows the chauffeur detaches himself from a knot of this kind standing there smoking and discussing intimately the affairs and foibles of their “masters” and “missies,” and trots around the corner to where the car is parked. The car arrives. One ambles leisurely downstairs, climbs in, and rolls away home. The club empties, except for the servants and those gay young bachelors, not gay this evening, who have missed out somehow in the plans of Shanghai hostesses.

Very few foreigners in China speak Chinese, while their servants always do, except when they are addressing the foreigner. They generally assume that their native tongue is a safe code, and one hears surprising remarks even in the undertone between the perfect attendants serving at the table. One makes it a practice never to listen, for it is a little startling, for example, when a lady of the dowager type has spoken somewhat testily to a boy, to see him incline very respectfully and then an instant later hear him say softly through the opening into the service pantry, “This old buffalo does not like the fodder.” The Chinese have no respect for a person with a short temper. They regard it as a final sign of bad breeding, and one speculates whether they may not be right. They pay respect for consideration and disrespect for temper.

At home, the boy has laid out dinner-clothes. One wears, with the black trousers, a white mess jacket, universally known as a “monkey jacket,” a natty little affair that stops at the waist with a little pointed tail at the back, a cummerbund, or sash, around the waist in lieu of a vest, and a soft pleated shirt with a soft turn-down collar. It is the coolest and most comfortable rig imaginable and is at once adopted by any visiting foreigner.

CHINESE-PARIS GOWNS

It is not so simple to describe what the ladies wear. They are a riot of colour, with all the styles of the world to draw from at first hand, all the wonderful fabrics the Chinese make in addition to those from home. Patient and capable house tailors, right at hand, make dresses and then still more dresses, and all at the most astonishingly low cost, in the aggregate. The house tailors are unique. One gives the tailor an illustration from Vogue, an older dress for measures, and the material, and in a day or two he achieves a creditable near-Paris gown.

This is the diary of a lady’s day in Shanghai: “I rode this morning, and then had tiffin at Margie’s where Cora and Virginia came in and we played Mah-Jong from two o'clock until I had to rush home to dress. I asked them all to come to dinner. I didn’t phone the cook until after six, and I’m sure he borrowed three outside dinners to make up enough. I looked into the dining-room when I came home and saw tons and tons of strange silver and china….I hurried downstairs and mixed cool drinks. Outside, the sound of a coolie grinding away methodically at an ice-cream freezer, the cook being jovial, the boys beaming, indicated that we were going to have a large evening, and every one was happy. There was no sign that the cook thought an hour too short notice for six guests. As full half of the servants’ income is “squeeze” or graft on the household bills, a volume of supplies means loose control, and guests are a welcome sign to the household staff.

“The guests arrived. As each car passed the gate in the high wall of the compound, the gatekeeper announced it by a shout. The coolie opened the house door. The boys, efficiently and without hurry or confusion, as the guests entered, appeared at hand to take their wraps. Every one talked at once. A distinguishing mark of Shanghai’s social life is that one almost never hears a phrase, much less a conversation, worth recording. Every one is too busy playing to be serious. Boys in white gowns passed hors-d’oeuvres of all the spiced and seasoned relishes that ever were invented, until one imagined there could not be any dinner intended to follow. But dinner followed, most elaborately, with perfect service and a loud, cheerful sound of voices and laughter.

“The evening was not planned. It just happened. Wives and husbands were carefully separated at table and remained so during the evening. In cars, by twos, they left the house and went down to the Carlton to dance. It was awfully crowded. There was a jazz orchestra, imported from the United States. It was as good an orchestra as any at home, and since foreign service has to be made attractive, it is perhaps fully twice as well paid. Every one in Shanghai, except the missionaries, is there sometime during the week. Some of the “regulars” come every evening. Lines of social cleavage are apparent between the tables around the dancing floor, but not on the dancing floor itself.

“Later, we moved on. Into the motors again and to the Astor. After a while, away again and to Maxims, but it is very much like the Carlton at either place, and finally, in the small hours, some one of the party suggested the dance halls out on Zikkawei Road in Frenchtown, the Crest and the Delmonte. Those are just beginning to wake at midnight, and from then until morning they get more riotous. It is the equivalent of slumming. Then we see at gay tables friends who have come on for the same reason as we—to see the sights. Even after this, our party felt no depression. The very air was fuzzy after the long evening, and so we laughed and chatted as we had five o’clock breakfast of ham and eggs, plebeian, prosaic, comfortable ham and eggs”

Out there, it is a gay, hectic, carefree life. Ask any man who has been there if he would return. He would. If he would not, he was one of the lame, the halt, or the really conscientious. Such never really taste Chinese life, but those who have tasted are bound to it. They can not escape from its call if they would, and they would not if they could—, and so that is the colour of Shanghai.